|

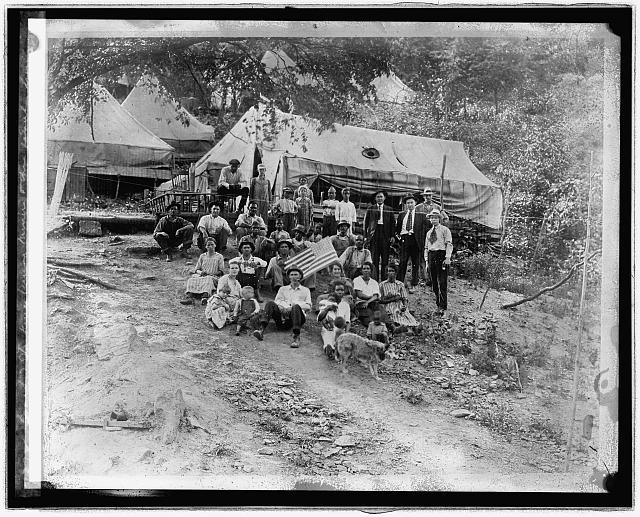

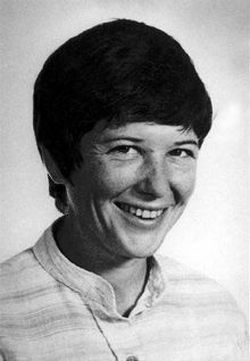

Fannie Sellins is back! I'm working on the final edits of her biography scheduled for release in 2016, nine years and many revisions after I began the project. Fannie Sellins entered my life via a Google search on American labor history back in 2007--In the Midst of Terror She went out to Her Work was one entry that turned up. Who could pass on that? Not me. The article by Mary Lou Hawse started like this: "Fannie Sellins was a labor organizer -- and from all accounts, she was an exceptional one. But she paid with her life." Suffice it to say, I was off like a bloodhound tracking scent and by the end of the day, I was determined to write a book about this woman.  Ita Ford Ita Ford She reminded me of Ita Ford, one of the Maryknoll sisters brutally murdered by national guardsmen in El Salvador in 1980.Both women shared a love for the poor, selfless courage, and a focus on people's everyday needs while working for systemic change. Ita chose to work in El Salvador, where a small minority controlled the vast majority of the country's wealth and most people lived in poverty. She was fully aware of the death squads raining violence on those who spoke out against the system, including the Catholic Archbishop of El Salvador Oscar Romero who was assassinated while saying Mass. Ita believed deeply in Romero's words, "one who is committed to the poor must risk the same fate as the poor. And in El Salvador we know what the fate of the poor signifies: to disappear, to be tortured, to be captive and to be found dead." In 1913-14, Fannie Sellins made her home among the destitute miners’ families in the nonunion coal fields of West Virginia. The United Mine Workers Journal called her an "Angel of Mercy," who went into the miners' homes, encouraging their wives and caring for the sick and dying. "Whenever there was a strike, with its inevitable suffering, Mrs. Sellins was found, caring for the women and children through the dark days of the struggle." Threatened with arrest for urging miners to join the union, Fannie said, “The only wrong that they can say I have done is to take shoes to the little children in Colliers who need shoes. And when I think of their little bare feet, blue with the cruel blasts of winter, it makes me determined that if it be wrong to put shoes upon those little feet, then I will continue to do wrong as long as I have hands and feet to crawl to Colliers.” When the miners’ union was crushed in West Virginia, Fannie moved to Pennsylvania’s Black Valley, they called it the Black Valley. The name sprang from the fighting between labor unions and mine owners. Fighting so fierce, they called it war. Labor war. In late summer 1919, miners struck Allegheny Coal and Coke in Brackenridge, PA. Fannie was warned to leave town if she valued her life. She stayed. She walked the picket lines with the men and rallied strikers to stick it out.  Women at Fannie Sellins Funeral, St. Peter’s Church, New Kensington PA Women at Fannie Sellins Funeral, St. Peter’s Church, New Kensington PA She tried to keep peace, while the two sides heckled each other and often came to blows. One afternoon an argument broke out between sheriff’s deputies and an unarmed miner. A crowd gathered, including Fannie, seeing deputies club, then shoot and kill the man. She shouted for the lawmen to stop. They turned on her, gunning her down as she tried to herd nearby children to safety. Ita and Fannie did not give their lives in some grand gesture of generosity and selflessness, they simply got up each morning and did the work that was before them. For Ita, it was driving people where they needed to go in the rocky hills of El Salvador, or delivering medicine and food. For Fannie, it was helping a poor woman in labor or encouraging workers to believe they deserved better. They stood with the poor and powerless with such integrity that those with power and wealth could not allow them to live. For more on the men who ordered Ita's death click here. For the rest of the story on Fannie, you'll have to wait for the book. :)

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|