|

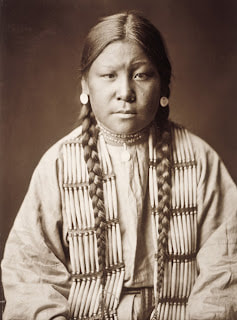

Yes, that Custer, General George Armstrong Custer killed in the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn. We know the men, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, who whupped the general that day, but what of the women? The names and faces of the native women of the Great Plains are all but lost, erased from mainstream history. That's why the story of Buffalo Calf Road Woman is so important. It gives us a glimpse into the lives of native women at the height of the "Indian Wars," the US effort to subdue and corral the Plaines Tribes or annihilate them. There is no known photo of Buffalo Calf Road Woman. She may have looked similar to the unidentified Cheyenne woman in this photo, sometimes mistakenly identified as her. The Northern Cheyenne kept a vow of silence for more than "100 summers" until 2005, when a tribal elder stood up and told how Buffalo Calf Road Woman attacked Custer. One incident in the life

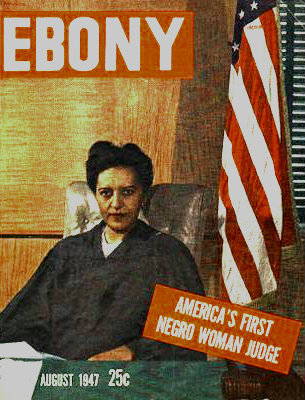

Congress set a side a particular day, August 14th, to honor and remember the Navajo Code Talkers, Native American men who developed codes using the Navajo language to help win WWII. Still, even now, much of the code talker story remains shrouded in history. The Navajo Code Talkers contributions to the victory in WWII was kept secret until the war department declassified the program in 1968. Since then, their story has become known around the world, but code talkers came from as many as 34 Native Nations, and the first to serve were Choctaw, in the First World War! If not for a chance circumstance, when an US officer overheard two Choctaw soldiers speaking their language, WWI might have turned out differently. Jane Bolin paid little attention to the history she was making as the first Black woman judge in America, and more to the needs of kids, a human resource we can't afford to waste. In 1931, with segregation prevalent throughout the country, Jane Bolin became the first Black woman to graduate from Yale Law School, where racist students thought it good fun to slam doors in her face.

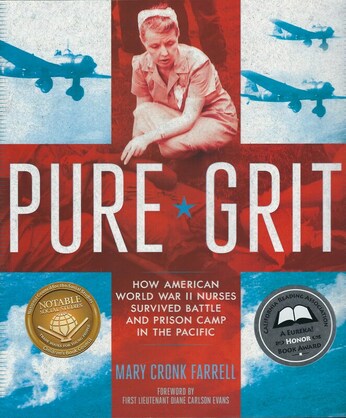

Though black and female, Jane armed herself with her degrees, ambition and desire to do good and moved to New York City. She became the first black woman to join the New York City Bar Association, and the first to work in the city’s legal department. “Everyone else makes a fuss about [all these firsts], but I didn’t think about it, and I still don’t,” she told the New York Times in a 1993 interview. “I wasn’t concerned about first, second or last. My work was my primary concern.” Her 40-year career in New York City's Domestic Relations Court primarily focused on protecting the city's children, particularly under-privileged youngsters, a human resource she insisted American could not afford to waste. Judge Jane Bolin may not have cared about making history, but her legacy challenges and inspires us today. Belle was nine-months pregnant when the Japanese Army took her husband prisoner. She was a military wife in the Philippines in 1941 when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. At the time Americans feared the Japanese would invade the west coast of their homeland. That didn't happen in Washington, Oregon, California or Alaska. But the Japanese did invade the Philippines where American forces were woefully unprepared. The story of the American surrender to the Japanese and the U.S. military nurses taken POW is told in my book Pure Grit. But today's story focuses on one young woman, expecting her fourth child, who got horrible news. Her husband was one of 75-thousand starving and disease-stricken soldiers, U.S. and Filipino, forced to surrender to the Japanese Imperial Army.

I cannot imagine what went through Belle Valentine's mind. On the one hand, her husband was alive. But could he stay alive while a prisoner of an army known for its brutality? The Japanese had utter contempt for soldiers who would surrender rather than fight to the death. I know one thing. Belle was determined to do everything in her power to save him.

I mentioned a short time ago, how the kaleidoscope of events in 2020 sent me into a bit of an emotional spin, prompting me to think more deeply about personal and public affairs.

​ One thing on my mind is media literacy. For the month of May, I'll be engaging people on social media about the topic of media literacy. I'll have Instagram Live interviews with experts and resources for adults and teens. |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|