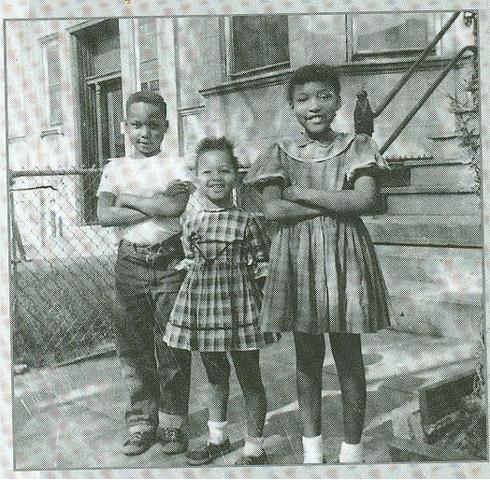

The first African-American woman in space set her eyes on the stars as a child growing up on the south side of Chicago. She has not changed her view since. Her story may set your eyes on the stars as well. Mae Jemison went from being a fan of the original Star Trek, to appearing in the movie Star Trek: The Next Generation. From earning a chemical engineering degree at Stanford to getting her medical degree at Cornell. From practicing medicine in a Cambodian refugee camp, to orbiting the earth in a space shuttle. Mae Jemison went from being the first African-American Woman in space to an entrepreneur set on developing the capability to send people like you and me to another star. Oh, and resolve climate change while she's at it. “Capabilities—notice that I didn’t say a launch date?” Dr. Jamison told qz.com. “Why is that important? Because all the capabilities that are required to go beyond our solar system are the very same things that we need to survive as a species on this starship [earth]. What’s the main capability we need? Sustainability.” It seems rather than dreaming of possibilities, Mae Jemison has always believed in done deals. As a young girl during the heyday of the American space program, she closely followed details of the Gemini, Mercury and Apollo programs. "I always assumed I would go into space," Mae says. "Not necessarily as an astronaut; I thought because we were on the moon when I was 11 or 12 years old, that we would be going to Mars—I'd be going to work on Mars as a scientist." (Below, Mae at center, her brother Ricky and sister Ada Sue) Mae's kindergarten teacher suggested she consider being a nurse. Mae put her hands on her hips and insisted, no, she'd be a scientist. "And that's despite the fact that there were no women, and it was all white males—and in fact, I used to always worry, believe it or not as a little girl, I was like: What would aliens think of humans? You know, these are the only humans?" Many years later, after earning her M.D., working in the Peace Corps and taking up a general medical practice in Los Angles, Mae remembered her childhood plans.  “I still wanted to go into space. So I applied. Picked up the phone. I called down to Johnson space center I said I would like an application to be an astronaut. They didn’t laugh. I turned in the application." She was accepted, one of fifteen astronaut candidates in 1987, and completed training the next year. "I didn’t even think about the fact of whether I would be the first African-American woman in space or anything like that…it didn’t even cross my mind. I wanted to go into space. I couldn’t care if there had been a thousand people in space before me or whether there had been none. I wanted to go.”  September 12, 1992, the space shuttle Endeavour launched from Kennedy Space Center in Florida and Mae Jemison was strapped into a seat on board. She served as the science mission specialist on the cooperative venture with Japan, doing experiments in life and material sciences, including bone cell research. "I felt like I belonged right there in space," Mae says. "I realized I would feel comfortable anywhere in the universe — because I belonged to and was a part of it, as much as any star, planet, asteroid, comet, or nebula." These days Mae Jemison works to ramp up enthusiasm for travel beyond our solar system and wants the general public to be more involved than they were in the days of the Apollo program's race to the moon.

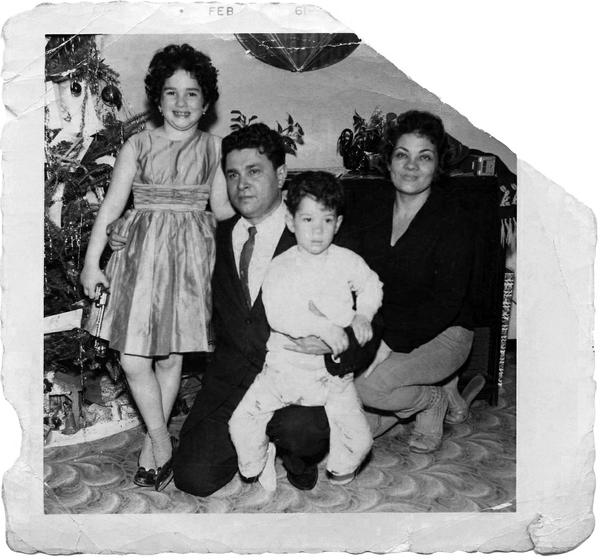

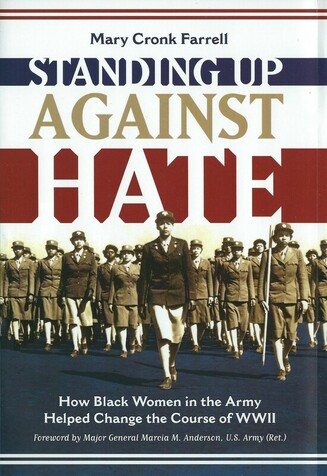

To that end, she's founded The Earth We Share, an international science camp to increase middle school and secondary school student’s science literacy and problem solving skills. "Science literacy is not about people becoming professional scientists, but rather being able to read an article in the newspaper about the health, the environment and figure out how to vote responsibly on it." In addition, with seed money from the federal government, Dr. Jemison started The 100-Year Starship to encourage the basic research necessary for sending humans to another star. Jemison and other scientists working to come up with perpetual, clean energy for interstellar travel believe their work could provide breakthroughs to deal with climate change here on earth. Sources: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_168.html https://www.pbs.org/video/secret-life-scientists-mae-jemison-i-wanted-go-space/ https://qz.com/1159940/mae-jemisons-100-year-starship-project-is-actually-about-climate-change-planning-not-space-travel/ http://teacher.scholastic.com/space/mae_jemison/index.htm  My newest book launched yesterday, giving me a little flutter of excitement as I scrambled my egg for breakfast, pretended to work, but mainly checked twitter and Facebook. Even at the grocery, I levitated a bit pushing my cart through the produce section. But at the end of the day, the thrill of pub date always falls short of the high I get when I discover a great story, dig for the details and choose the right structure and words to tell it. That's what I love. Of course, I'm incredibly grateful and proud of the book on the shelf. And it's outright awesome to hear from readers. But a book launch doesn't happen every day. Me, sitting here writing, that's what happens everyday. And when I write a story like the following, my brain sparks, my blood rushes and I might as well be flying. It feels that thrilling. So please, read on. One little fact I discovered by accident started this story. I happened to read that the mother of Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor served in the Women's Army Corps (WAC) during World War II.  Celina Sotomayor with her daughter, Judge Sonia Sotomayor. White House photo. Celina Sotomayor with her daughter, Judge Sonia Sotomayor. White House photo. Of course, that caught my interest, due to my latest book about the origins of the WAC in the 1940s. My search for more information on Celina Sotomayor's military service turned up other information that completely took over my focus. For I'd found the extraordinary story of heartbreak and resilience that helped shape the first Latinx on our country's highest court. But let's begin with Celina Baez's enlistment in the WAC. in fled extreme poverty in Puerto Rico to join the WAC in 1944. Like many soldiers during WWII, she lied about her age to enlist at 17. She spoke little English and didn't know a soul in Georgia where she reported for basic training. Celia brought with her a fervor for the value of education as a stepping-stone to improving one's circumstances. Possibly stemming from the way her parents protected the one pencil the family possessed, divvying its use between their five children. Celina didn't let a lack of school supplies impede her academics. She studied by playing teacher to a number of trees behind her home, pointing at each with a stick and calling them by name to recite her lessons. This, in a country were the literacy rate stood at 39-percent and families earned an average of $200 per year, adjusted for inflation that's about $3590. But Celina didn't earn her high school diploma after her mother died and her father abandoned the family. She was raised by an older sister until joining the WAC at a time when few women of color felt welcome in the U.S. Army. There she trained to become a telephone operator. When the Senate confirmed Celina's daughter as a Supreme Court Justice in 2009, it surely proved the American dream had come true for Celina. But every story has its conflicts and challenges, its dark night of the soul, and so does Celina's.  After the war, Celina fell in love with a young Puerto Rican immigrant employed as a welder, Juan Luis Sotomayor. Juan came from a warm extended family that gathered for feasting, dominoes, singing and dancing. He wrote poetry, cooked fabulous food and knew how to make the ordinary fun. After Celina and Juan married, she continued her education, earning a high school equivalency certificate. In 1954, she and Juan welcomed little Sonia and three years later a son, Juan, Jr. In her early marriage, Celina worked at Prospect Hospital in the South Bronx as a telephone operator, then turned her studies to the medical field becoming a Licensed Practical Nurse. The Sotomayor's happy life started to crumble when her husband began to drink heavily, and her young family fell victim to the disease of alcoholism. Celina and Juan started to fight, loudly and often. Tension filled their home. Work became a refuge for Celina as she signed up for night and weekend shifts at the hospital. Young Sonia didn't understand how addiction was tearing apart her family, nor why her mother seemed cool and distant, while her father was fun to be around. She blamed her mother for her father's alcoholism. When Sonia was 9 and Juan, Jr. 6, their father died of a heart attack, leaving Celina with no savings. She went to work six days a week, arriving home to make her children dinner, then retreating behind the closed doors of her bedroom to cry out her grief. She mourned the death of her husband, her marriage and loss of financial stability. And she was grief-stricken over all that she'd lost to alcoholism years before, the wonderful man she'd fallen in love with and the life they'd dreamed of together. Celina fell into depression and months passed before she gathered herself together and rose from her grief to nurture her children and supervise their education, which now seemed more important than ever. She sacrificed and saved to keep her children in private school and purchased the only set of Encyclopedia Britannica in their Bronx housing project. Her son Juan remembers studying for hours at the kitchen table. "We studied when we came home, it was natural and we enjoyed it. There was never any negative energy about it because Mom used to say, 'Just do the best you can'."  Celina went back to school herself, when Sonia was in high school. She studied with her teens at the kitchen table, pursuing a dream. At 46 she got her degree and became a registered nurse. During all these years, her daughter Sonia had not come to terms with her feelings about her mother and the troubles the family went through in her early years. In the autobiography she published after joining the Supreme Court, Sonia wrote, "though my mother and I shared the same bed ... she might as well have been a log, lying there with her back to me." "It wasn't until I began to write this book, nearly fifty years after the events of that sad year, that I came to a truer understanding of my mother's grief," she wrote. "It was only when I had the strength and purpose to talk about the cold expanse between us that she confessed her emotional limitations in a way that called me to forgiveness." Showing affection didn't come naturally to Celina who'd been an orphan from age 9 and lived through a contentious marriage. She told her daughter, "'How should I know these things, Sonia? Whoever showed me how to be warm when I was young?'" Sonia had paid tribute to Celina the day President Barack Obama had chosen her as a nominee for the Supreme Court. “I have often said that I am all I am because of her, and I am only half the woman she is.” Sonia said before the president and a national television audience. “I thank you for all that you have given me and continue to give me.” Understandably proud of both her children, Celina says she expected them to do well, "but I never envisioned them becoming what they are." Her son earned his medical degree from New York University and owns a private practice specializing in allergy and asthma diagnostics. Celina retired in the early 1990s, though she continued for many years using her nursing skills to aide neighbors in her apartment complex, on call for whoever was sick and rang the doorbell. One neighbor says Celina even “removed my cat’s stitches.” Celina is now retired in South Florida with her second husband Omar Lopez. I hope you enjoyed this story as much as I did. Let me know what you think in the comment section below. I've checked out the audio version of "My Beloved World," and from my local library and hope I can get to it before it's due. Sources: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/05/28/us/politics/28mother.html https://www.npr.org/2013/01/12/167042458/sotomayor-opens-up-about-childhood-marriage-in-beloved-world  Standing Up Against Hate is out in the world! It's the story of how black women in the U.S. Army changed the course of WWII. It's an honor and a privilege to tell the stories of these courageous women. Here's a sample of feedback I've gotten on the book. ★Starred Review, School Library Connection: "A nonfiction writer for youth audiences, Farrell settles in to explain with depth and precision the fight black women faced both in and out of the military as World War II surged. Focused specifically on black women in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), the book profiles several key figures, including Major Charity Adams who commanded the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. "In addition to the deft writing, images are presented every few pages that reveal a score of brave women who persevered despite suffering discrimination. The women had to proclaim their equality in the face of segregation in the mess hall and in dispatching the unit overseas. "The text also details how some servicewomen were jailed for disobeying orders or even beaten by civilians while wearing their uniforms. Organized chronologically, the text is accessible for middle school and high school historians who are intrigued by institutional racism or women in the military for research. It profiles milestones in the 6888th’s preparation and deployment, providing a well-researched understanding of the time period for black women in the military. "The book is a gem that profiles an underrepresented narrative in American history." Available at the links below or your favorite bookstore.  1st Lieutenant Dovey Johnson 1st Lieutenant Dovey Johnson Watching record numbers of women sworn into the U.S. Congress, I couldn't help but think of the bitter congressional debate during World War II about establishing the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps. The controversy was really about where women did or didn't belong. "This war is not teas, dances, card parties and amusements," Congressman Clare Eugene Hoffman of Michigan said. "You take a poll of the honest-to-goodness women at home, the women who have families, the women who sew on the buttons, do the cooking, mend the clothing, do the washing, and you will find there is where they want to stay—in the homes.” Apparently, 150,000 women did not want to stay at home, which is how many volunteered for army service during WWII. One of those was Dovey Johnson of Charlotte, North Carolina, one of the first African American woman commissioned as a WAAC officer. Read more about Dovey in Standing Up Against Hate. (Pre-order here.) The book comes out January 8th. Dovey worked as an assistant to Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, who was the only African American in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's cabinet. When Congress approved the WAAC, Dr. Bethune demanded that black women, not only be allowed to enlist, but to be trained as officers right along beside white women. At first, Dr. Bethune's logic fell on deaf ears, but she convinced Eleanor Roosevelt that black women deserved equal opportunity, and the First Lady convinced her husband. Dr. Bethune had long been a family friend, but when Dovey went to work for her, she had no idea the plan was for her to join the army! Here's an excerpt of an interview with Dovey Johnson Roundtree seven decades later. She talks about rumors the women of the WAAC were meant to be "companions" for the soldiers. This interview was conducted by the National Visionary Leader Project in 2009. You can see the full interview here.

Teachers: Check out this lesson plan you can use with students to look at gender roles in America in the 1940s and how the idea of women serving in the military threatened prevailing attitudes about the duties of women. |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|