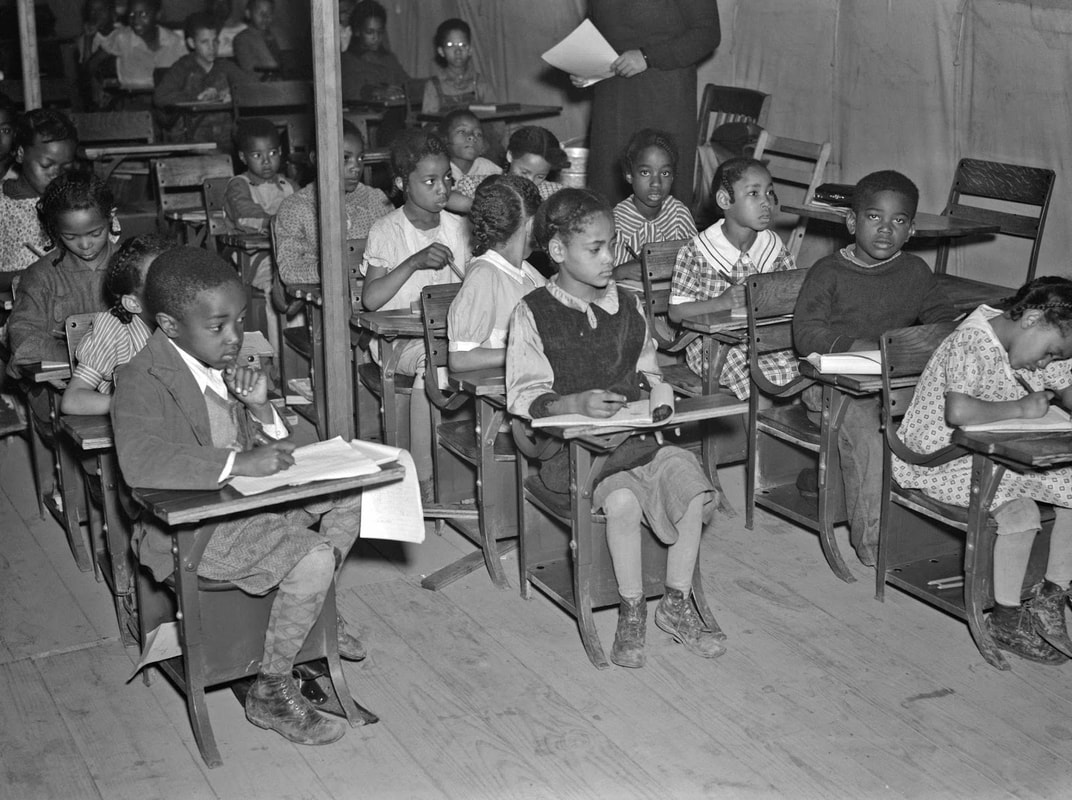

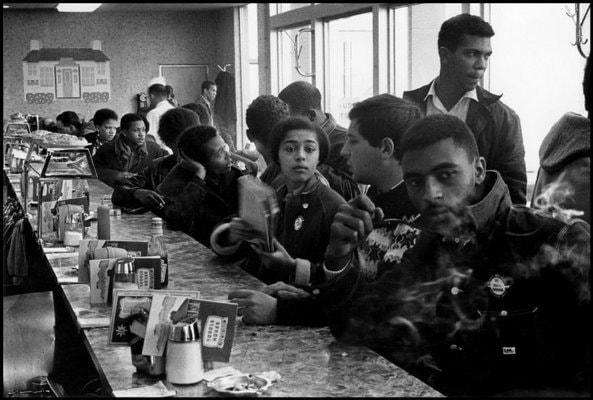

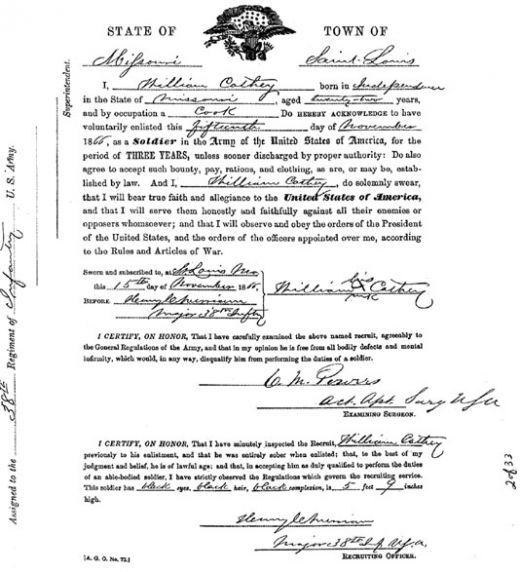

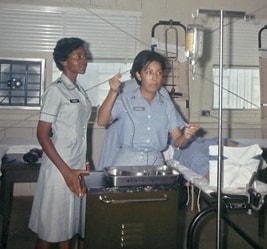

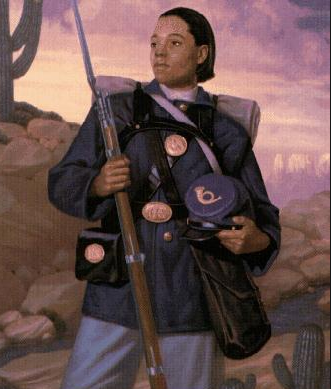

If only we could bottle it. She grew up working in the tobacco fields of Wake County, North Carolina. Her parents had a large family, ten children, because sharecropping required many hands and all-consuming labor. How did Clara Leach make the leap from the Jim Crow south to Brigadier General in the U.S. Army? She wrote the story of her life after retirement to set the record straight. "I was increasingly encountering people who assumed that I was successful because I was born with a “silver spoon” in my mouth or I just “got lucky.” At age five Clara cooked and tended younger siblings in a house with no electricity or running water, while her parents and older siblings grew and harvested tobacco for a white landowner. Soon Clara graduated to field work. That included planting, hoeing, pulling weeds, walking the rows "topping" off the buds to stimulate growth, and picking worms off the leaves and squishing them. "Growing tobacco...is a very difficult crop...labor intensive," Clara says. "So my father and mother had ten children, and we were all employed full time on that farm in tobacco." Photo: The daughter of an African American sharecropper at work in a tobacco field in Wake County, North Carolina. Credit: Dorothea Lange, July 1939. First ingredient Clara's parents believed in education as well as hard work. And though she missed a lot of school due to farm work, Clara skipped two grades and graduated at sixteen, salutatorian of her class. The painful experience of prejudice at her segregated school in Wake County launched the attitude that would carry Clara from the soil of North Carolina to the halls of the Pentagon. "Many members of the African-American community considered dark skin ugly. Unattractive. Undesirable. That message came across loud and clear in terms of which students were favored by teachers, and by other students," Clara says. "When I raised my hand, the teacher would never call on me." "Instead, a kid with straight hair and fair skin always got picked. Some of them were really smart, but so was I. It was all part of a warped value system that some black people still embrace today-the closer you are to being white, the better off and more beautiful you are." Clara's mother told her beauty was skin deep and that what others thought of her didn't matter. "It's what you think of yourself that matters," she said. It was a good lesson but it didn't take away the sting of being passed over. Clara made a decision. Elixir for success: "I spent a lot of time getting even smarter, because I knew knowledge could never be snatched from me, regardless of whether I was high yellow or black as midnight," says Clara. Those early snubs and slights I experienced due to skin color further motivated me to excel. They lit a fire under me that drove me to succeed not just at academics, but at whatever endeavor I tackled." She went college at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University to study nursing. There Clara took part in the the famous Greensboro sit-ins at the Woolworth's lunch counter. She told an interviewer for the Women Veterans Historical Project about her experience with non-violent protest. "When people push you, spit on you, curse you and do those kinds of things, it’s very difficult not to raise your hand. But in reality, when you think about it, it’s quite a powerful thing to be able to sit and do nothing while people do that."  To fund her last two years of college, Clara signed up for the Army Student Nurse Program scholarship. After graduation in 1961. she entered the U.S. Army Nurse Corps as a 2nd Lieutenant. Her values of hard work and a positive attitude continued to serve her well as she met obstacles as a woman and a black in the army. "Obstacles are not really there to stop one’s progress. They are really opportunities for us to decide how we will overcome them to reach our goals. If we keep the goal in mind, then we can decide if we will go over, under, around or through the obstacle to accomplish it." Essential:  In 1965, Clara became a medical-surgical nursing instructor at Fort Sam Houston where she became the first woman in the army to earn the Expert Field Medical Badge. She continued to rise in the ranks and continue her education, the first nurse corps officer to graduate from the Army War College and the first woman to earn a Master’s Degree in military arts and sciences from the Army’s Command and General Staff College. Assigned to Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Clara trained a generation of nurses and then became the first African American to serve as vice president and chief of the department of nursing at the hospital. In 1987 she was promoted to Brigadier General and named Chief of the Army Nurse Corps and Chief of Army medical personnel.  The list of Clara Leach Adams-Enders' accomplishments in the army is long and impressive, including formal distinctions like the Distinguished Service Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster and informal such as recruiting minority student nurses at Walter Reed. She led the Army Nurse Corps through two major combat operations, Just Cause and Desert Shield/Storm. Clara is also known for her remarkable warmth and humility. Retiring after a 34-year career in the army, she wrote a book about her life to inspire others, My Rise to the Stars: How a Sharecropper's Daughter Became an Army General. She also runs a management consulting firm Cape Incorporated with the mission of helping organizations manage their people with care and enthusiasm. With hard work, education and the right attitude, Clara Leach Adams-Ender made the journey from sharecropper's daughter to the highest ranks of the U.S. Army. Her success also stands on the shoulders of those who trod this path before her. Thousands of African American women overcame obstacles to serve with distinction in the U.S. Army during WWII. Read their story in Standing Up Against Hate: How Black Women in the Army Helped Change the Course of WWII. Here's a warm-up to get you excited for my new book. Standing Up Against Hate: How Black Women in the Army Help Change the Course of WWII tells the story of the first African American women to join in the U.S. army. At least I thought it did. Turns out a black woman soldier in the 1860s beat them to it.  Painting by William Jennings, U.S. Army Profiles of Bravery Painting by William Jennings, U.S. Army Profiles of Bravery Cathey Williams disguised herself as a man and enlisted in Company A of the Thirty-Eighth Infantry Regiment in St. Louis, November 1866. She switched her name to William Cathey, and after what must have been a cursory exam, the army surgeon declared her fit for duty. Private Cathay was 22-years-old and had actually been serving as an cook for the army throughout most of the civil war. Cathey told her story to a reporter for the St. Louis Daily Times in 1875. "My Father a was a freeman, but my mother a slave....While I was a small girl my master and family moved to Jefferson City, [Missouri]....When the war broke out and the United States soldiers came to Jefferson City they took me and other colored folks with them to Little Rock. Col. Benton of the 13th army corps was the officer that carried us off. I did not want to go. He wanted me to cook for the officers, but I had always been a house girl and did not know how to cook." She had little choice. She learned to cook. At sixteen, swallowed by the union army, Cathey saw the Battle of Pea Ridge, a major battle of the Civil War fought near Leetown, northeast of Fayetteville, Arkansas, after which her unit traveled to Louisiana. "I saw the soldiers burn lots of cotton and was at Shreveport when the rebel gunboats were captured and burned on Red River." As a servant under General Phillip Sheridan, Cathey saw the soldiers' life on the front lines as his army marched on the Shenandoah Valley. After the war, African American soldiers were posted to the Western frontier, where they battled Native Americans to protect settlers, stagecoaches, wagon trains and railroad crews. They became known as “Buffalo Soldiers,” apparently so-named by Native Americans, though history's a little thin on when and why. After working for the army throughout the war, it's little wonder Cathey came up with the scheme to enlist as the fighting came to a close. With cunning and courage she found a way to survive when opportunities for black women were few to none. As a Buffalo Soldier, Cathey learned to use a musket, stood guard duty and went on scouting missions. After serving at Fort Riley, Kansas for some months, her company marched 563 miles to Fort Union, New Mexico. Official reports show Buffalo Soldiers were often sent to the most bitter posts and suffered racist officers, severe discipline and crummy gear, food and shelter. In two years of service, mostly in New Mexico, Cathey needed hospital care four different times for illnesses ranging from "the itch" to rheumatism, yet maintained her secret. Cathey enlisted for three years, but after two, she was tired of army life and wanted out. She told the St. Louis reporter, “I played sick, complained of pains in my side, and rheumatism in my knees. The post surgeon found out I was a woman and I got my discharge." All indications are that she was a good soldier. After her honorable discharge, Cathey worked as a civilian cook and washer woman. Until she could not longer work due to diabetes and nerve pain which required the amputation of her toes. She was unable to walk without a crutch.

In 1891, Cathey petitioned for a veterans pension and benefits. The government rejected her claim, not because she was a woman, that was never argued. The army doctor who examined her found her to be fit, not disabled enough for benefits. There's no record of the life or death of Cathey Williams following that denial of benefits. Sources: http://blackhistorynow.com/cathay-williams/ http://www.buffalosoldier.net/CathayWilliamsFemaleBuffaloSoldierWithDocuments.htm |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|