Elzbieta Ficowska Elzbieta Ficowska Life has a way of coming full circle, sometimes in what seems a miraculous way. Take the case of Elzbieta Ficowska, an employee at a nursing home in Warsaw, Poland. You might call Elzbieta’s entire life a miracle. She was born Jewish in Nazis-occupied Poland. With hindsight, we know her chances of survival were close to zip. The Nazi’s forced Warsaw’s Jews, 400,000 people, nearly a third of the city’s population, into a space of sixteen blocks and barricaded them behind 7-foot walls, guarded by soldiers. Called the Warsaw Ghetto, it became a holding pen for the Treblinka death camp. Each month baby Elzbieta clung to life in the Ghetto, five thousand others perished from sickness and starvation. Anyone caught helping a Jew to escape would be shot, moreover, their entire family would be shot. In this desperate situation, that surely seemed hopeless, up sprang Zegota, the underground Polish resistance.  Irena Sendler Irena Sendler One member, a young Catholic woman, code name Jolanta obtained access to the Ghetto with forged papers identifying herself as a nurse. She smuggled food, clothing and medicines to the people inside under the pretense of conducting inspections for typhus. In July of 1942, when Elzbiata was six months old, Jolanta came to visit with the child’s mother. There is no record of the conversation between the two young woman, but the result was that Elzbiata was drugged so that she would not cry and placed in a wooden tool box that belonged to a Gentile carpenter. He had a work pass into the Jewish section, and that day when he drove his truck out through the Nazi checkpoint, his tool box of illegal cargo lay hidden under a load of bricks.  Jolanta, whose real name was Irena Sendler, organized a network of trusted friends that rescued 2,500 Polish Jewish children like Elzbiata from the Warsaw Ghetto and certain death. Irena said it was heartbreaking for the mothers to let their children go. “They ask if I can guarantee their safety. I have to answer no….We witnessed terrible scenes. Father agreed, but mother didn't. Sometimes they would give me their child. Other times they would say come back. I would come back a few days later and the family had already been deported. ” Once outside the gates, the children dropped their Jewish identities and were taken to Roman Catholic convents, orphanages and homes. Irena used every way she could imagine to get the children to safety. Some were carried out in sacks of potatoes, some sedated in coffins, older children learned Catholic prayers and hymns and were led out through underground corridors where the Polish police had been bribed to allow their passage. Others exited under the floorboards of an ambulance, a barking dog on board to drown their cries. Danger always lurked close by. One of the children waited by a gate in the dark, counting to 30 after the German soldier on patrol passed, then ran to the middle of the street where a manhole cover mysteriously opened and the boy escaped into the sewers to eventual freedom. In October 1942, Elzbiata did not find out she was adopted and Jewish until her adoptive mother told her when she was 17. “She told me, much later, that my birth mother called from time to time on the telephone, and that she would ask that the telephone receiver be passed to me, at least for a moment. She undoubtedly longed for me. Perhaps she wanted to assure herself that I still existed and to hear my babbling... In October 1942, she telephoned for the last time.” On the night of October 20, 1943, the Gestapo pounded on Irena's door. They took her Pawiak prison and asked her to implicate the others in her network and to give up the children’s identities. She refused, and was tortured, repeatedly, the bones in her legs and feet broken, her body scarred. Finally, she was sentenced to death. At nearly the last minute Zegota was able to bribe a German guard, who listed Irena as executed and left her in the woods. Irena lived in hiding until the end of the war. At that time, she hoped to reunite the children with their families. She had kept a complete list of all 2,500 Jewish children and their new identities. She buried them in jars under a tree in a neighbor's yard across the street from the German barracks. Most of the parents, however, had been gassed at Treblinka.  Irena Sendler Irena Sendler Irena lived to be 98, and it was near the end of her life when she lived in a nursing home that she and Elzbieta met again. Life coming full circle in a what may seem a miracle, but is an event that stemmed from Irena's great courage and willingness to risk her own life to help save others. Irena explained it like this, "We who were rescuing children are not some kind of heroes. That term irritates me greatly. The opposite is true – I continue to have qualms of conscience that I did so little. I could have done more. This regret will follow me to my death." For decades, Irena lived in obscurity until a 1999 project based learning assignment at a high school in Kansas. For more about the young women who brought this heroine to the attention of the world, watch a video here... For a two-minute video including an interview with Irena click here... Irena learned compassion from her father, one of the first Polish socialists and a Catholic physician. Many of his patients were poor Jews. When a typhus epidemic broke out in 1917, he was the only doctor willing to Jews. He contracted the disease. His dying words to seven-year-old Irena were... "If you see someone drowning, you must jump in and try to save them, even if you don't know how to swim." Sometimes what seems miraculous is a phenomenon of human courage and compassion. I'd love to hear what you think. Please leave a comment below. And if you think this story is worth reading, please use the icons to share it with your friends.  Through a stroke of luck, I heard Anthony Doerr read the first few short chapters of ALL THE LIGHT WE CANNOT SEE at a literary festival in Spokane last year. I was hooked by the specificity and beauty of his writing, and the tension of the story. Still, I put off reading the book all year while it became a finalist for the National Book Award; a #1 New York Times bestseller; was named a best book of the year by the New York Times Book Review, Powell’s Books, Barnes & Noble, NPR’s Fresh Air, Entertainment Weekly, the Washington Post, Seattle Times and the Guardian, just to name a few. I feared a tragic ending, after all, it’s a war story. I finally overcame my trepidation, and now I highly recommend the book. It touches on all the grand themes of life that we struggle to understand. It’s the story Marie-Laure, blind from the age of 6 who lives with her father in Paris, where he is a locksmith at the Museum of Natural History. The museum is her second home as she grows up, learning the mysteries and beauty of nature through her fingertips. She was particularly fascinated by one professors collection of shells. Dr. Geffard teaches her the names of shells--Lambis lambis, Cypraea moneta, Lophiotoma acuta--and lets her feel the spines and apertures and whorls of each in turn. He explains the branches of marine evolution and the sequences of the geologic periods; on her best days, she glimpses the limitless span of millennia behind her: millions of years, tens of millions of years. Intertwined with the girls’ story is that of a German orphan boy Werner, incredibly bright, but trapped in a mining town that produces raw materials for the Nazi war machine. Werner is 8-years-old when he discovers a rudimentary radio in a junk heap. For three patient weeks, he studies it and works on it until he gets it to work. Open your eyes... The only legal radio programs spout Nazi propaganda, but Werner secret listens to a Frenchman broadcast of a science lesson for children. Open your eyes, concluded the man, and see what you can with them before they close forever, and then a piano comes on, playing a lonely song that sounds to Werner like a golden boat traveling a dark river, a progression of harmonies that transfigures Zollverein: the houses turned to mist, the mines filled in, the smokestacks fallen, an ancient sea spilling through the streets, and the air streaming with possibility. It is these tenuous radio waves that eventually connect Marie-Laure and Werner, though it is years later when she is a 16-year-old working with the French Resistance and he is a soldier in the German Army using his gift for math to root out illegal radio transmitters.  Walled city of Saint-Malo occupied by Germany in WWII Walled city of Saint-Malo occupied by Germany in WWII Marie-Loure and her father have fled Paris for the walled city of Saint-Malo on the coast of Brittany. Throughout the book we “see” from the point-of-view of the blind girl, but here at the ocean, her perceptions become especially keen as she encounters the live creatures that were empty shells in the museum. The reader is reminded of words Werner heard over the radio years earlier. The brain is locked in total darkness of course, children, says the voice. It floats in a clear liquid inside the skull, never in the light. And yet the world it constructs in the mind is full of light. It brims with color and movement. So how, children, does the brain, which lives without a spark of light, build for us a world full of light?  On his website, Anthony Doerr explains the meaning of the title, All The Light We Cannot See. It’s a reference first and foremost to all the light we literally cannot see: that is, the wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum that are beyond the ability of human eyes to detect (radio waves, of course, being the most relevant). It’s also a metaphorical suggestion that there are countless invisible stories still buried within World War II — that stories of ordinary children, for example, are a kind of light we do not typically see. Ultimately, the title is intended as a suggestion that we spend too much time focused on only a small slice of the spectrum of possibility. - from Doerr’s site So, yes, it ends as a war story often ends, but the read is worth it. I recommend it to older teens as well as adults. The relationship between Marie-Laure and her father, and that which she develops with her great-uncle Etienne are transformative and the book is worth reading for them alone, but there is so much more that is difficult to put into words. The intricate structure crafts myriad threads together, a haunting and spectacular weaving of the highest and lowest of human nature. Have you read it? What do you think? With much thanks to Aria Antiques, Curious Expeditions, San Fransisco, CA  The church filled with the beautiful, yet somber, music and chanting of In Paradisum and the pungency of incense, as the draped casket moved up the aisle from the sanctuary. I was saying good-bye to my friend Kay for the last time and my grief spilled into tears as the truth settled in my heart. She was really gone. In that instant, I didn’t think I could bear it. But somehow I did, and the questions rose, the same questions that niggle every funeral or memorial service—why didn’t I appreciate this person more while she was alive? Why did I take for granted her wonderful qualities, which are all we can talk about now? Why do I go through so many days not realizing how thrilling it is to be alive and the preciousness of people around me. Every time, I vow I will change. Several weeks, or maybe just days later, I’m still the same person I was before. Maybe my goal of wholesale change is impractically dramatic. Maybe I imagine a transformation so complete it is fantasy. It’s seems so obvious that significant change is realized in small steps, but we tend to shoot for the stars without building a spaceship. ...but we tend to shoot for the stars without building a spaceship.  I’d known Kay and her husband for more than 15-years. During that time we regularly shared the nitty-gritty of our lives and our travels on the spiritual path. Kay was lively, with a playful, sometimes irreverent sense of humor, and helped me see when I was taking myself too seriously. She was both highly-educated and wise, but paid attention to me as if at any moment I might impart some valuable knowledge. She was happy for me in my accomplishments large and small, and shared my disappointments and struggles. My failings fell lightly into the well of her compassion, and her capacity for accepting me without judgment set off ripples of healing. In her eyes I saw myself and I was a thing of beauty. Kay’s ready smiles, hugs and hospitality were a well that never ran dry. I hadn’t known Kay and her husband very long, when I told my husband, “That’s the partnership I want for us when we’re 65.” They spoke to each other in tones resonant with affection, humor and mutual respect. When their eyes met, they sparkled. They shared tender glances, thoughtful conversation, and a unity of purpose. My husband and I agreed, if we didn’t begin to build this relationship now, we would not have it later. ...if we didn’t begin to build this relationship now, we would not have it later. As the years passed, we realized Kay and her husband were also teaching us how to experience the uncertainties, frailties and losses inherent in aging. They didn’t conceal their vulnerability, made no pretense of winning the fight against sickness, aging and death. Kay was a model for me in so many ways, a mentor, a friend and an inspiration. And it was clear at her wake and funeral—I did not hold the lone lottery ticket for Kay’s love. She saw a homeless woman at the drop-in center where she volunteered with the same eyes that she saw me. And Kay was a woman of action. What her eyes saw, she did something about, something practical, something that made tomorrow a little better than today. To understand the force for good Kay wielded in this world, requires mathematics of the heart. Take what Kay gave me, times it by every person she knew and multiply. ...requires mathematics The question now: Will Kay’s dying be her final lesson for me? Or can I capture some thread of her life, some texture of the woman she was, and with small, steady stitches, piece it into my daily routine. Can I continue to learn and grow through her example and help make tomorrow’s world a little better than today’s?

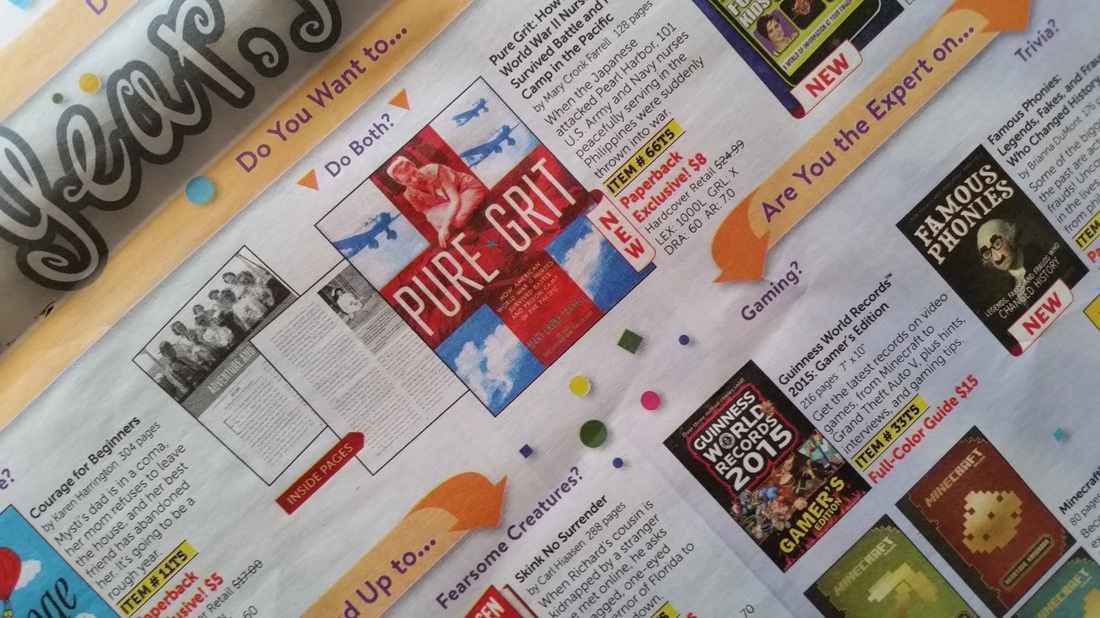

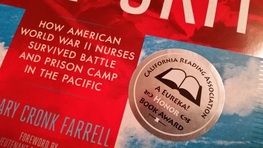

Will I have the courage to learn from love? Do you?  My 9-year-old self is squealing with glee! My book PURE GRIT appears in this month's Scholastic Reading Club form in schools across the country. This may be the most exciting thing yet in my writing career. When my elementary school teachers passed out those book club flyers, I couldn't wait to look through and see what books were available. I usually could only afford one book each month, so sometimes the decision was rough going. Nothing compared to seeing the box arrive, my teacher slitting the tape, the books coming out and one getting passed into my hands. Maybe my dream of writing books for kids started right there. Scholastic buys the rights to publish cheaper paperback editions of books for the reading club, to make it easier for kids to own their own books. Teachers pass out the order forms and students can bring money to school or their parents can purchase the books online.  Scholastic awards points to teachers for all the books their students purchase. Teachers can use these points to buy books for their classrooms. I'll take this opportunity to acknowledge that a book is a team effort, and to thank the team that produced PURE GRIT.  Since the advent of e-mail, going to the mailbox has lost most of its excitement and gravitas. So it was a red letter day when I received the envelope from my publisher containing a strip of silver stickers. I had know that PURE GRIT had been named a 2014 Eureka! honor book, but it really hit home when I stuck that sticker on the cover. The California Reading Association established the Eureka! Nonfiction Children’s Book Award to celebrate and honor nonfiction children’s books and to assist teachers, librarians, and parents in identifying outstanding nonfiction books for their students and children. Click here to see all the books on the list. Also, thank you to readers, librarians, teachers, and Veteran's organizations--I am humbled by your response to the book. |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|