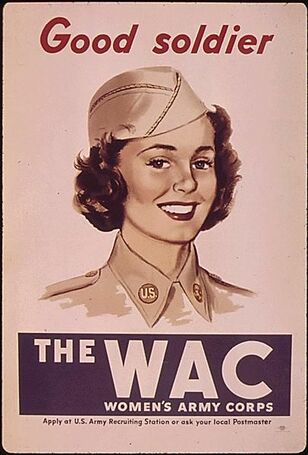

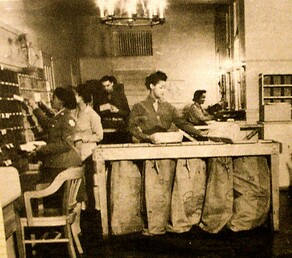

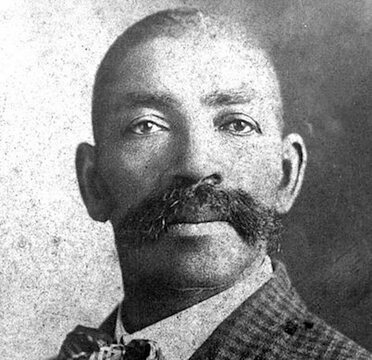

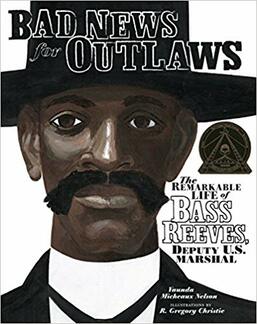

You just never know where your research will take you. Searching for information on a surviving member of the the all-black 6888th Battalion spotlighted in Standing Up Against Hate: How Black Women in the Army Helped Change the Course of WWII, I discovered the debate surrounding a growing market for black memorabilia. I've never actually seen one of the hitching post figures of a cartoonish young black boy with exaggerated features, which I thought was now universally considered racist. But I've learned a lot about racism in America in the last couple years and maybe shouldn't have been surprised by the Little Black Sambo cookie jars and Mamie salt and pepper shakers being sold on E-bay. I also didn't expect to find them while researching Fran McClendon, a 101-year-old African American Veteran of WWII.  In late summer of 1943, the Allies won important victories in Italy and New Guinea, and the Nazis and Japanese were retreating. But the war was far from over and the U.S. Army needed more manpower. Congress voted to raise the status of women in the army from supplemental support to official members of the military. All over the country, the Women's Army Corps recruited volunteers, telling women they could "free a man to fight" and help win the war. Fran McClendon went with a group of girl friends to talk with a recruiter and they all decided to enlist. A year later, Fran was assigned to the 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. It would be the only unit of black women deployed overseas during the war.  Fran would end up serving 26 years in the military, first the army, then the air force, posted Korea and Vietnam, and retiring at the rank Major. But it was her WWII assignment in Birmingham, England, where she developed an appreciation for fine crystal and china. The Black WACs' job in England was to sort a huge backlog of mail and re-direct it to soldiers in the field. They worked in shifts around the clock because the packages and letters were crucial to troop morale. But Fran and the others did have days off to explore the town. Birmingham citizens welcomed the WACs and invited them to tea in their homes and out to restaurants. Crystal and china were everywhere. Fran saw it in shop windows at the weekend markets and soon gained a love of fine craftsmanship. Many years later, after her military career, Fran went into the antique business. “I love the study of the glass industry and china industry,” she told a reporter recently. Yes, recently. To this day, she runs an antique shop, the Glass Urn in Mesa, AZ, where she deals mostly in American crystal, but has some glassware from Ireland, Sweden and Germany. Over the years, the Glass Urn has carried a large variety of antiques, occasionally items made in the image of a black person. These types of collectibles, almost always demeaning, have been manufactured in America since the beginning of the slave trade and remained common and popular up through the 1950s. At times, Fran McClendon has questioned whether to sell certain items of black memorabilia, but she considers them art. “My husband and I loved art and in art you find all kinds of things."  Where Fran sees art, some see historical artifacts that can be educational, and other find these black collectibles racist and offensive. As an African-American history professor, Donald Guillory, has mixed feelings about black memorabilia. The items can spark conversation about the negative portrayal of blacks, which might be a teachable moment. “If it’s anything other than learning the context or teaching about it, why would you want something that offensive, or that overtly offensive, in your home?” He concludes. What I found startling when I happened upon this topic, is the burgeoning popularity of black memorabilia, so much so, that replicas are now being manufactured in China. A documentary on the topic debuted earlier this month on PBS. Read about it here... Or watch the one-hour documentary Black Memorabilia here... As for Fran McClendon, after forty-years of selling antiques, she's preparing to retire. “I’m downsizing,” she said. “I want to do things and I know I can’t hold on to everything.” I hope she holds on to at least one set of glassware that reminds her of Birmingham, England, and her time in the Women's Army Corps. For further interest, there's a book that goes into some depth about how these racist depictions of blacks continued to be reinvented over the decades of American history. Mamie and Uncle Mose: Black Collectibles and American Sterotyping. Sources: http://www.eastvalleytribune.com/local/mesa/mesa-antiques-store-owner-liquidating-life-s-work/article_8d388c76-3163-11e2-b6e4-0019bb2963f4.html https://www.pinalcentral.com/arizona_news/antique-dealers-see-controversial-african-american-memorabilia-as-part-of/article_eed8b251-42b2-5978-8fc8-682fa9eefb32.html White guys like John Wayne personify our image of the American West, so it might surprise you to know that roughly one in four cowboys riding the range was black. On Saturday night when they went to town, these men couldn't stay in hotels or eat in restaurants. I'm not sure if they could drink and play cards in the saloons, but during the workweek, their skill with a horse, a rope and a gun, could gain them a level of respect. In the three decades following the Civil War at least 25 (probably more) African American men served as deputy U.S. Marshals for the U.S. government. There's some evidence to suggest that one of those rough-riding, straight-shooting black lawmen formed the basis for the iconic Lone Ranger. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves grew famous in the late 19th Century, during his 30-years pursuing and arresting bandits and murders throughout what was called Indian Territory. The former slave has some distinct resemblances to Lone Ranger of radio, comic book, TV and movies. Bass was born a slave in Arkansas in 1883, and was taken to Texas his owner William Reeves as an 8-year-old boy. When the Civil War broke out, Reeves' son joined the Confederate Army and took Bass with him to the front lines as a servant.  U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves Before the war's end, Bass escaped, heading west to what was then called Indian Territory and now the State of Oklahoma. Historians say there he learned horsemanship and tracking skills from Native Americans and also became handy with Colt 45 and a rifle. After emancipation, Bass was just one of many black men looking for work. “Right after the Civil War, being a cowboy was one of the few jobs open to men of color who wanted to not serve as elevator operators or delivery boys or other similar occupations,” says William Loren Katz, a scholar of African-American history. The Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Chickasaw tribes had been forcibly moved from their homelands to "Indian Territory" where they governed themselves, but the federal government was responsible for rounding up the lawless element hiding out there, thousands of thieves, murderers and fugitives. The call went out to hire 200 deputies for the job, and Bass Reeves fit the profile. Strong, steady, 6-foot-2, with a deep voice and commanding presence, he was appointed the first African-American lawman west of the Mississippi.  U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves U.S. Deputy Marshal Bass Reeves By all accounts, he was one of the best, serving for more than 30-years in relentless pursuit of lawbreakers. The Oklahoma City Weekly Times-Journal reported, “Reeves was never known to show the slightest excitement, under any circumstance. He does not know what fear is.” True to the mythical code of the West, Bass Reeves never drew his gun first. Though many outlaws aimed to shoot him, their bullets always missed. He was never even grazed by a bullet. Reeves admitted he shot and killed 14 men, but all in self-defense. He's credited with bringing in 3,000 outlaws alive. More than once, showing up at the District Courthouse in Fort Smith with ten or more prisoners in tow. From the “Court Notes” of the July 31, 1885, Fort Smith Weekly Elevator: “Deputy Bass Reeves came in same evening with eleven prisoners, as follows: Thomas Post, one Walaska, and Wm. Gibson, assault with intent to kill; Arthur Copiah, Abe Lincoln, Miss Adeline Grayson and Sally Copiah, alias Long Sally, introducing whiskey in Indian country; J.F. Adams, Jake Island, Andy Alton and one Smith, larceny.” Though he couldn't read or write, Bass Reeves always knew which arrest warrant matched his man, and he used his brains, as well as his brawn and firepower to enforce the law. He often wore disguises to catch criminals unaware, and that may be the first clue that connected Bass with the famous "masked man." He rode a large light gray horse and gave out silver dollars as a calling card, similar to the Lone Ranger's trademark silver bullets. At least one biographer says the deputy marshal at times worked with a Native American partner tracking criminals. And like the Lone Ranger, he demonstrated an unshakable moral compass, even arresting his own son on a murder charge, after which the son was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.  So far, historians have not proven the Lone Ranger was based on the exploits of Bass Reeves, but the most convincing piece of evidence seems to be that many of the prisoners he captured and turned into authorities at Fort Smith, went to serve their jail sentences in Detroit, the city where George Trendle and Fran Striker created the character of the Lone Ranger. A children's biography Bad News for Outlaws: The Remarkable Life of Bass Reeves, Deputy U.S. Marshal, won the 2010 Coretta Scott King Award. It was written by Vaunda Micheaux Nelson and illustrated by R. Gregory Christie. One reviewer on Goodreads says, "This is a children's book, but still very informative." Because, of course, most children's books are not informative. (heavy sigh)  For more reading on the topic, check out Gary Paulson's historical novel for teens called the Legend of Bass Reeves: Being the True and Fictional Account of the Most Valiant Marshal in the West. Publishers Weekly called it a "compelling fictionalized biography...Effectively conveying Reeve's thoughts and emotions, the author shapes an articulate, well-deserved tribute to this unsung hero. Sources: https://blackdoctor.org/482030/this-week-in-black-history-the-real-lone-ranger-was-a-black/ https://www.history.com/news/bass-reeves-real-lone-ranger-a-black-man |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|