|

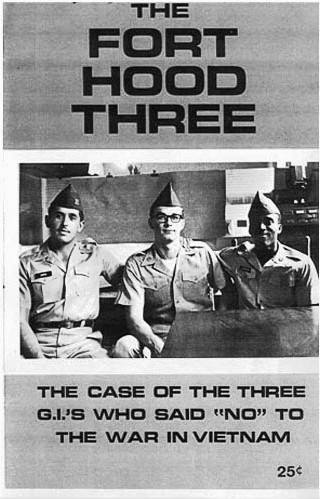

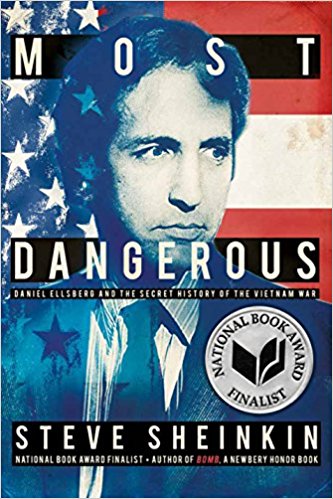

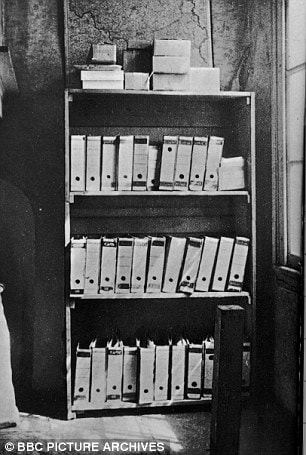

The Post. Have you seen it yet? It's a great movie for a news junkie like me. And freedom of the press is a timely topic, as is women making their voices heard. But like most Hollywood movies based on true events, a lot of the story gets left out. The Spielberg movie starring Meyrl Streep and Tom Hanks tells the story of The Post's Katharine Graham's decision about whether to publish the Pentagon Papers in 1971. She knew she could face prison and financial ruin. The New York Times had already scooped The Post, but a federal injunction barred the newspaper from continuing to publish the top secret documents proving four U.S. presidents had lied about the U.S. policy in Vietnam. Rarely in those times did a woman own and run a newspaper, but for dramatic appeal, the movie makes Katharine appear inexperienced and weak-kneed. To be sure, she was a well-known society woman, but Katharine had been running the company for eight years by 1971. She'd had keen interest in the news business from a young age and worked as a journalist in San Francisco before becoming a wife and mother.  A more important and major fact glossed over in the movie, is that the Pentagon Papers were not the first evidence that the government was lying about the Vietnam War. The soldiers on the ground were some of the first to make these accusations, and the major news sources did not make it a priority to investigate. In 1966, three soldiers, U.S. Army Privates David Samas and Dennis Mora, and Private First Class James A. Johnson refused orders to ship out to Vietnam saying: “We have been in the army long enough to know that we are not the only G.I.’s who feel as we do. Large numbers of men in the service do not understand this war or are against it. No one uses the word ‘winning’ anymore because in Vietnam it has no meaning. Our officers just talk about five or ten more years of war with at least half-million of our boys thrown into the grinder.” They came to be known as The Fort Hood Three, and they stood firm even as they faced court marital and went to prison. Released from military prison three years later, Samas, Mora and Johnson found little had changed in Vietnam. But hundreds of their comrades, active-duty service members had joined the anti-war movement by the late 1960's. During the Vietnam war years, 1966 and 1971, more than five-hundred thousand U.S. military servicemen deserted the armed forces. In unprecedented numbers, entire units refused to go into battle. Soldiers and veterans published more than 200 underground anti-war newspapers presenting abundant evidence of government deceit. One mainstream journalist talked to hundreds of U.S. troops in Vietnam and became convinced the government was lying about the war. He wrote to Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman J. William Fulbright.  Senator J. William Fulbright shown with Senator Wayne Morse during the hearings. Senator J. William Fulbright shown with Senator Wayne Morse during the hearings. Fulbright launched hearings in February 1966 that included retired generals and respected foreign policy men. CBS television interrupted regular programming to air these hearings live, and the nation tuned in. People started to see through the screen of deception. Until... CBS caved to pressure from President Lyndon Johnson. Also, the network, didn't want to lose money by preempting afternoon soap operas, cementing the decision to stop broadcasting the hearings. That was five years before Katherine Graham came under heat from Defense Secretary Robert McNamara over the Pentagon Papers. The Post is getting great reviews, and I recommend it as good entertainment that raises issues very relevant today. Of course, we can't depend on Hollywood movies to teach history, but I am now inspired to watch the documentary film about Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers, for a more complete understanding. Click below to watch the trailer.  I also recommend a recent book on the subject for teens, Most Dangerous: Daniel Ellsberg and the Secret History of the Vietnam War written by acclaimed author Steve Sheinkin. The book received five starred reviews, and according to Kirkus Reviews, the book's "lively, detailed prose rooted in a tremendous amount of research, fully documented. . . Easily the best study of the Vietnam War available for teen readers.” In addition, if you know a history teacher, let them know about this role playing activity that helps students understand the issues that led to the Vietnam War. Next up, I'm hoping to see Murder on the Orient Express for some escapist entertainment.  New research suggests the 70-year-old story of someone snitching to the Germans and betraying Anne Frank and her family may not be true. Evidence points to the possibility that the secret annex hiding eight Jews for more than two years may have been discovered during a raid by officers investigating ration coupon fraud.  For the last decade, researchers at the Anne Frank House have been compiling a digital data base of new discoveries. They distill facts from diaries, books, archive material and government documents. They've interviewed dozens of concentration camp survivors, Frank family members, classmates and business associates. Looking at the evidence, they ask new questions. ''The question asked has always been Who betrayed Anne Frank and the people in hiding? This explicit focus on betrayal, however, has limited the perspective on the arrest. Scenarios based on other premises have never been examined at length." Researchers took a new tactic, for the first time asking 'Why did the raid on the Secret Annex take place, and on what information was it based?" They took another look at Anne's famous diary. Particularly, what she wrote about two men she called "B" and "D" arrested for dealing in illegal ration cards “so we have no coupons.” This led researchers to Dutch Judicial records where they found two men from the building had been arrested earlier in 1944, and then released.  Since the end of World War II, at least five people have come under suspicion for betraying the hiding place at Amsterdam 263 Prinsengracht. Despite official investigations and biographers' theories, there is no convincing proof of a culprit. The new research isn't solid proof either, but it opens the possibility that investigators stumbled upon Anne Frank by chance. Anne, her sister Margot and their parents, Otto and Edith were caught August 4, 1944 along with four other Jews hiding with them. The bookcase pictured here had been constructed to camouflage entry into a part of the building out of view from the street. Of the eight Jewish people seized, only Otto Frank survived the concentration camps. Anne died of typhus at age 15 at Bergen-Belsen in Germany. In 2015, researchers at the Anne Frank House gathered evidence that Anne and Margot died a month earlier than previously believed, in February 1945, rather than late March of that year. Anne Frank House researcher Erika Prins told the Guardian: “When you say they died at the end of March, it gives you a feeling that they died just before liberation [April 15, 1945]. So maybe if they’d lived two more weeks …” Prins said, her voice trailing off. “Well, that’s not true any more.” Below: After liberation, female German camp guards are forced to unload a truck full of bodies of dead prisoners at Bergen-Belsen, April 1945. George Rodger—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images. The earlier March 31 date of Anne’s death was set by Dutch authorities after the war when they did not have the resources to establish an exact date. The new evidence includes statements from a friend who saw Anne in Bergen-Belsen and remembered the Frank sisters showing signs of typhus in early February. Dutch health authorities say typhus deaths happen around 12 days after the first symptoms.

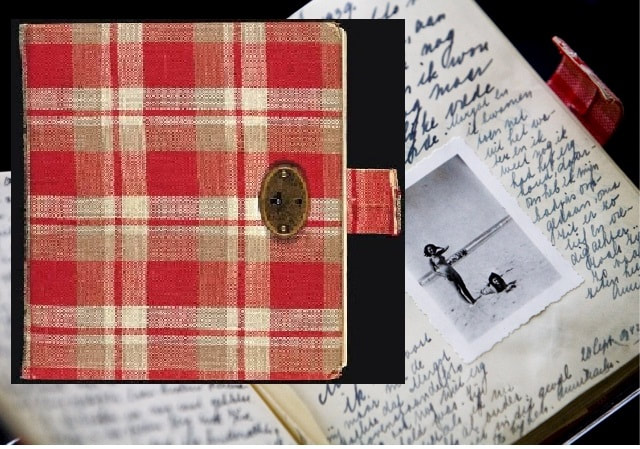

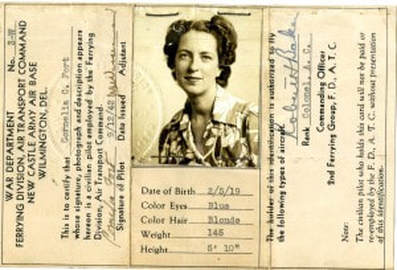

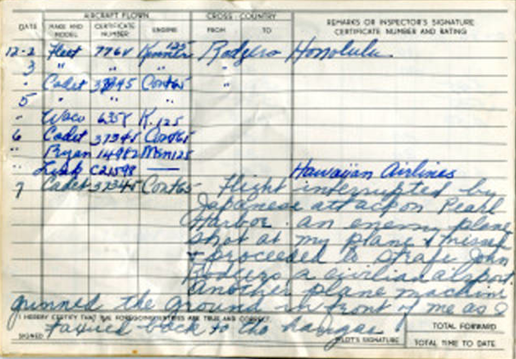

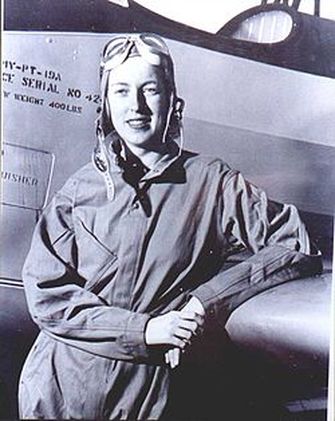

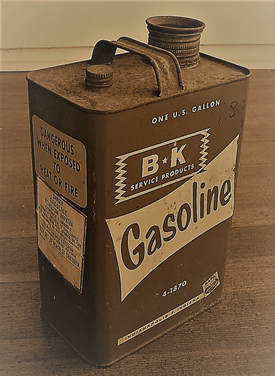

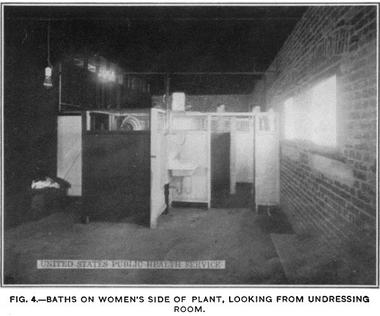

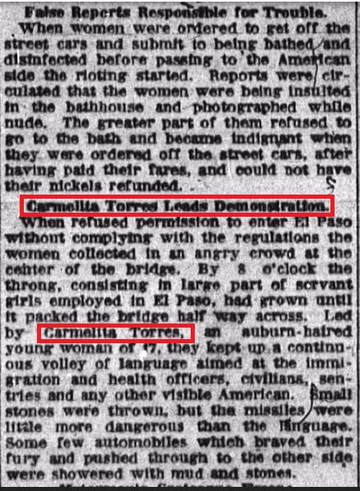

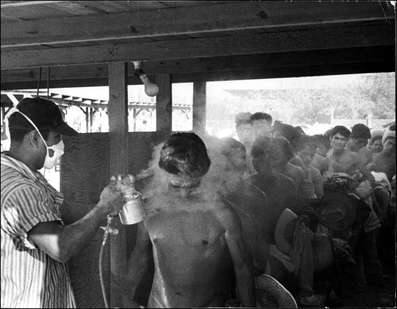

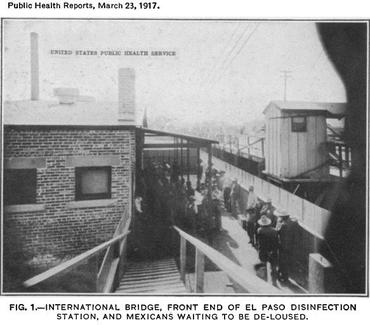

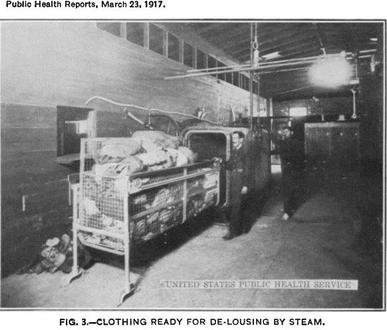

“In view of this, the date of their death is more likely to be sometime in February. The exact date is unknown,” the researchers said. In the words of Bergen-Belsen survivor Rachel van Amerongen, "One day they simply weren’t there any more." Seven decades after her death, Anne Frank stands as an example of resistance and courage in the face of inhuman cruelty and persecution. To view a short video showing friends talking about seeing Anne in Bergen-Belsen, click here...  Cornelia Fort was born to wealth and privilege, but in a time and place that prescribed her a very narrow role in life. Yet she made bold choices push boundaries and lived of life of daring and adventure few women would even dream of. Would she have made the same choices, if she'd known it would lead to hear at 24? Growing up in a luxurious mansion built in 1815 on the banks of the Cumberland River in Tennessee, she was expected to become a Southern debutante, attend society functions, marry and have children. At eighteen, Cornelia wanted to attend Sarah Lawrence College where young women could design their own course of study. Her father at first refused to allow her to apply to that "liberal northern school" and she was sent to Ogontz School for Young Ladies. In her first major rebellion against the "proper" role assigned to her, Cornelia got her mother to help change her father's mind. She was finally allowed to leave the "oppressive atmosphere" and transfer to Sarah Lawrence, where she graduated with a two-year degree. Cornelia's next bold move challenging the strictures of women's lives in the 1940s,  At age five, with her father and three older brothers, Cornelia saw a daring pilot perform acrobatics in the sky. It appeared so dangerous, Dr. Rufus Fort made his sons promise ( as one story goes, swear an oath on the family bible) they would never fly. Later, when Cornelia made her first solo flight, one brother chided her for breaking a promise to their father. But Dr. Fort had not thought to ask his daughter not to fly. She was hooked from her very first time in the sky, saying “It gets under your skin, deep down inside.” Cornelia Fort became the first female flying instructor in all of Tennessee in 1940. The next year she got a job in Hawaii teaching defense workers, soldiers and sailors to fly. In November 1941, Cornelia wrote home (her father had died more than year before). "If I leave here, I will leave the best job that I can have (unless the national emergency creates a still better one), a very pleasant atmosphere, a good salary, but far the best of all are the planes I fly. Big and fast and better suited for advanced flying. On December 7, 1941, she was in the sky with a student pilot when a small plane nearly collided with them. Cornelia grabbed the controls and saved their lives. Later, she said the plane “passed so close under us that our celluloid windows rattled violently and I looked down to see what kind of plane it was. The painted red balls on the tops of the wings shone brightly in the sun. I looked again with complete and utter disbelief. Honolulu was familiar with the emblem of the Rising Sun on passenger ships but not on airplanes.” “Then I looked way up and saw the formations of silver bombers riding in. Something detached itself from an airplane and came glistening down. My eyes followed it down, down, and even with knowledge pounding in my mind, my heart turned convulsively when the bomb exploded in the middle of the harbor. I knew the air was not the place for my little baby airplane and I set about landing as quickly as ever I could. A few seconds later a shadow passed over me, and simultaneously bullets spattered all around me.” See below the entry in Cornelia's logbook for that flight “Later, we counted anxiously as our little civilian planes came flying home to roost. Two never came back. They were washed ashore weeks later on the windward side of the island, bullet-riddled. Not a pretty way for the brave yellow Cubs and their pilots to go down to death.” Cornelia survived. And then stepped out of bounds again. She knew the risks when she became one of the first to volunteer for Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squad (WAFS) “I felt I could be doing something more constructive for my country than knitting socks. Better to go to war than lose the things that make life worth living.”  “Because there were so many disbelievers in women pilots, especially in their place in the army....We had to deliver the goods or else. Or else there wouldn’t ever be another chance for women pilots in any part of the service.” The WAFS ferried planes for the U.S. military during WWII, flying them from factories to points of embarkation. The group later merged with the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). The women pilots faced painful prejudice from some of the male pilots, who Cornelia said went "to great lengths to discredit them whenever possible.” The end came quickly, and far to soon. March 21, 1943, flying over Texas in a six-plane formation, Cornelia's Fort's wing tip was clipped by another plane. She crashed to the ground and died instantly. Cornelia was twenty-four, and became the first female pilot in American history to die in the line of duty, though the WAFS were not recognized as official military service members 1977.  A year prior to her death, Cornelia had written her mother, poetically describing how much she had loved life, loved green pastures and cities, sunshine on the plains and rain in the mountains, blue jeans, red wine, books, music and the kindness of friends. She wrote: If I die violently, who can say it was "before my time"? I should have dearly loved to have had a husband and children. My talents in that line would have been pretty good but if that was not to be, I want no one to grieve for me. I was happiest in the sky--at dawn when the quietness of the air was like a caress, when the noon sun beat down and at dusk when the sky was drenched with the fading light. Think of me there and remember me...Love, Cornelia. Cornelia's story reminds me we do not have time to be mired in self-doubt and regret. We make the best decisions we can without the benefit of knowing how they will unfold. Like Cornelia, I want to choose boldly and love life hugely. What about you?  When you hear the call: "Build the wall" take a moment and tell someone about Carmellita Torres. This 17-year-old girl sparked a protest on the Juarez/El Paso border in 1917 when customs officials ordered her to undress and submit to being doused with gasoline. The kind of guys in charge back then were the same kind of guys we have in charge now. So, unfortunately, Carmellita's courageous action did not bring change. But women's voices are being heard today, in way they never have been before. Carmellita Torres freely crossed the border from Mexico almost every day to work as a maid for an American family. She wasn't alone. Farmers and ranchers in the Southwest were completely dependent on Mexican labor. White families in El Paso could easily afford the wages they paid Mexican girls and women to do their cleaning and laundry. So many Mexicans from Juarez came to El Paso every day for work that a trolley was set up for them to ride across the Santa Fe Bridge between the two cities.  But El Paso Mayor Tom Lea, Jr. feared Carmellita and the other workers, whom he called "dirty, lousy, destitute," would carry lice and cause a typhus epidemic in his city. Rates of typhus infection were no higher in El Paso, than they were in other large American cities. But in January 1917, Mexicans were suddenly required to show a certificate to cross the border, a certificate indicating that "the bearer, ___ has been this day deloused, bathed, vaccinated, clothing and baggage disinfected.” Carmellita and the others were forced to strip nude for inspection, bathe, and be drenched in gasoline to kill any lice that might be on their bodies. Their clothing and shoes were fumigated and put through a steam dryer. The women were subjected to lewd comments and there were rumors that nude photographs of them were showing up in nearby bars. Sunday morning, January 28th, 1917, Carmellita reached the end of her trolley ride and was told to get off, take a bath and be disinfected. She refused. Carmellita convinced thirty other women on the trolley to refuse as well. By 8AM the crowd of protesters, mostly servant girls, grew to 200 and packed half the bridge. Some of the women stopped the trolley by laying down on the tracks. By noon some 2000 people stood with Carmellita.  Both Mexican and American soldiers showed up to subdue the crowd, and Monday morning it was back to fumigation as usual. There's little trace of Carmellita Torres in the pages of history. She's named in the newspaper for leading what came to be called "the bath house riots," and we know that she and eight other women were arrested and went to jail for "inciting riot" that day. Their stories may have been passed down the years orally, but the white men writing the newspapers and making the rules preserved a different story. The reporter for the El Paso Morning Times wrote that once Mexicans got familiar with the bathing process, they would welcome it. He said the Mexicans "came out [of the bath house] with clothes wrinkled from the steam sterilizer, hair wet and faces shining, generally laughing and in good humor." Raul Delgado, a man who went through the "cleansing" gave his description decades later. “An immigration agent with a fumigation pump would spray our whole body with insecticide, especially our rear and our partes nobles. Some of us ran away from the spray and began to cough. Some even vomited from the stench of those chemical pesticides…the agent would laugh at the grimacing faces we would make. He had a gas mask on, but we didn’t."  Bracero workers, hired for seasonal farm work, are sprayed with DDT after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border in 1956. (Smithsonian Institution) Bracero workers, hired for seasonal farm work, are sprayed with DDT after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border in 1956. (Smithsonian Institution) The risk of typhus has been used by both American and German leaders to whip up fear and prejudice against a segment of the population they wanted to deem inferior. The notion that Mexicans crossing into the U.S. for work each day would carry lice and cause a typhus epidemic, was used as an excuse to spray them with toxic chemicals. Men, women and children crossing the Juarez/El Paso border were doused or sprayed with chemicals like gasoline and DDT for more than 40-years. In Poland, the Nazis posted placards around Warsaw in 1940 declaring that Jewish people were infested with lice and carrying typhus. To protect the rest of the populace all Jews were required to move into a small section of the city that became the Warsaw Ghetto.  Author David Dorado Romo heard stories of fumigation from his aunt who had experienced it. When he started researching the subject at the National Archives, he discovered there was a lot more to the story and wrote about it in his book Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez, 1893-1923. "These records point to the connection between the U.S. Customs disinfection facilities in El Paso-Juárez in the 20s and the Desinfektionskammern (disinfection chambers) in Nazi Germany...." I discovered an article written in a German scientific journal written in 1938, which specifically praised the El Paso method of fumigating Mexican immigrants with Zyklon B," writes Romo. In 1939, the Nazis started using Zyklon B to fumigate people at border crossings and concentration camps. Later, they used Zyklon B pellets in the gas chambers at Auschwitz and other camps, not to kill lice, but people.  In 1917, after Carmellita's protest, the US/Mexican border was closed for the first time, customs officials prohibiting anyone from crossing without authorization. That is, without the required fumigation of their clothing, shoes and body. That year alone, 127,000 people suffered humiliation and were doused with toxic disinfectant at the El Paso end of the Santa Fe Bridge. This federal policy would promulgate a stereotypical negative view of Mexicans and their American descendants for decades to come. U.S. Public Health Service photos thanks to https://elpasogasbaths.weebly.com/ |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|