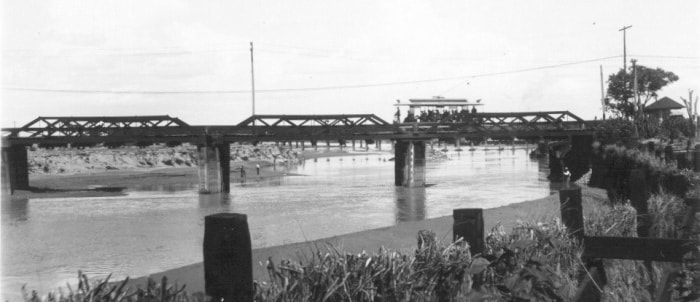

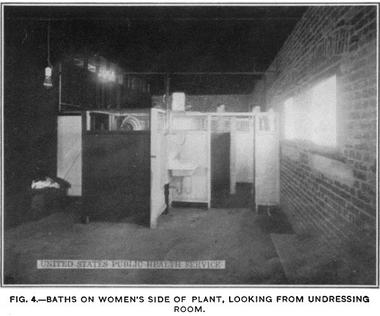

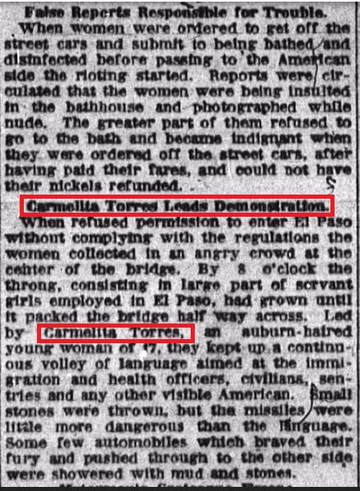

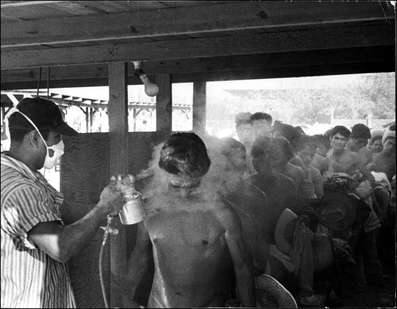

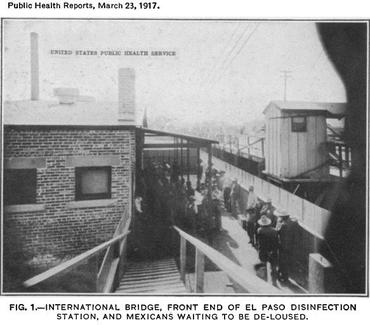

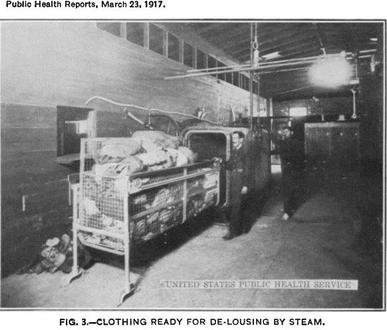

When you hear the call: "Build the wall" take a moment and tell someone about Carmellita Torres. This 17-year-old girl sparked a protest on the Juarez/El Paso border in 1917 when customs officials ordered her to undress and submit to being doused with gasoline. The kind of guys in charge back then were the same kind of guys we have in charge now. So, unfortunately, Carmellita's courageous action did not bring change. But women's voices are being heard today, in way they never have been before. Carmellita Torres freely crossed the border from Mexico almost every day to work as a maid for an American family. She wasn't alone. Farmers and ranchers in the Southwest were completely dependent on Mexican labor. White families in El Paso could easily afford the wages they paid Mexican girls and women to do their cleaning and laundry. So many Mexicans from Juarez came to El Paso every day for work that a trolley was set up for them to ride across the Santa Fe Bridge between the two cities.  But El Paso Mayor Tom Lea, Jr. feared Carmellita and the other workers, whom he called "dirty, lousy, destitute," would carry lice and cause a typhus epidemic in his city. Rates of typhus infection were no higher in El Paso, than they were in other large American cities. But in January 1917, Mexicans were suddenly required to show a certificate to cross the border, a certificate indicating that "the bearer, ___ has been this day deloused, bathed, vaccinated, clothing and baggage disinfected.” Carmellita and the others were forced to strip nude for inspection, bathe, and be drenched in gasoline to kill any lice that might be on their bodies. Their clothing and shoes were fumigated and put through a steam dryer. The women were subjected to lewd comments and there were rumors that nude photographs of them were showing up in nearby bars. Sunday morning, January 28th, 1917, Carmellita reached the end of her trolley ride and was told to get off, take a bath and be disinfected. She refused. Carmellita convinced thirty other women on the trolley to refuse as well. By 8AM the crowd of protesters, mostly servant girls, grew to 200 and packed half the bridge. Some of the women stopped the trolley by laying down on the tracks. By noon some 2000 people stood with Carmellita.  Both Mexican and American soldiers showed up to subdue the crowd, and Monday morning it was back to fumigation as usual. There's little trace of Carmellita Torres in the pages of history. She's named in the newspaper for leading what came to be called "the bath house riots," and we know that she and eight other women were arrested and went to jail for "inciting riot" that day. Their stories may have been passed down the years orally, but the white men writing the newspapers and making the rules preserved a different story. The reporter for the El Paso Morning Times wrote that once Mexicans got familiar with the bathing process, they would welcome it. He said the Mexicans "came out [of the bath house] with clothes wrinkled from the steam sterilizer, hair wet and faces shining, generally laughing and in good humor." Raul Delgado, a man who went through the "cleansing" gave his description decades later. “An immigration agent with a fumigation pump would spray our whole body with insecticide, especially our rear and our partes nobles. Some of us ran away from the spray and began to cough. Some even vomited from the stench of those chemical pesticides…the agent would laugh at the grimacing faces we would make. He had a gas mask on, but we didn’t."  Bracero workers, hired for seasonal farm work, are sprayed with DDT after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border in 1956. (Smithsonian Institution) Bracero workers, hired for seasonal farm work, are sprayed with DDT after crossing the U.S.-Mexico border in 1956. (Smithsonian Institution) The risk of typhus has been used by both American and German leaders to whip up fear and prejudice against a segment of the population they wanted to deem inferior. The notion that Mexicans crossing into the U.S. for work each day would carry lice and cause a typhus epidemic, was used as an excuse to spray them with toxic chemicals. Men, women and children crossing the Juarez/El Paso border were doused or sprayed with chemicals like gasoline and DDT for more than 40-years. In Poland, the Nazis posted placards around Warsaw in 1940 declaring that Jewish people were infested with lice and carrying typhus. To protect the rest of the populace all Jews were required to move into a small section of the city that became the Warsaw Ghetto.  Author David Dorado Romo heard stories of fumigation from his aunt who had experienced it. When he started researching the subject at the National Archives, he discovered there was a lot more to the story and wrote about it in his book Ringside Seat to a Revolution: An Underground Cultural History of El Paso and Juarez, 1893-1923. "These records point to the connection between the U.S. Customs disinfection facilities in El Paso-Juárez in the 20s and the Desinfektionskammern (disinfection chambers) in Nazi Germany...." I discovered an article written in a German scientific journal written in 1938, which specifically praised the El Paso method of fumigating Mexican immigrants with Zyklon B," writes Romo. In 1939, the Nazis started using Zyklon B to fumigate people at border crossings and concentration camps. Later, they used Zyklon B pellets in the gas chambers at Auschwitz and other camps, not to kill lice, but people.  In 1917, after Carmellita's protest, the US/Mexican border was closed for the first time, customs officials prohibiting anyone from crossing without authorization. That is, without the required fumigation of their clothing, shoes and body. That year alone, 127,000 people suffered humiliation and were doused with toxic disinfectant at the El Paso end of the Santa Fe Bridge. This federal policy would promulgate a stereotypical negative view of Mexicans and their American descendants for decades to come. U.S. Public Health Service photos thanks to https://elpasogasbaths.weebly.com/ Comments are closed.

|

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|