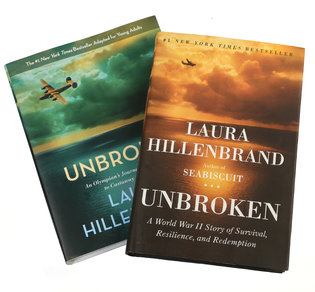

A twitter storm erupted and blew around the blogsphere the past couple days after The New York Times published the article To Lure Young Readers, Nonfiction Writers Sanitize and Simplify, by Alexandra Alter. At issue is Laura Hillenbrand’s new edition of her best seller UNBROKEN and a scene where a Japanese guard tortured and killed an injured duck. "I know that if I were 12 and reading it, that would upset me," Ms. Hillenbrand said in the Times article. A growing number of adult writers are writing cut down versions of their books for this market. Alter wrote “these slimmed-down, simplified and sometimes sanitized editions of popular nonfiction titles are fast becoming a vibrant, growing and lucrative niche” The words “simplified and sometimes sanitized” caused much of the flack.  YA Author Beth Kephart blogged: Let's first acknowledge what many young readers are capable of, which is to say, books rich with moral dilemma and emboldened by ideas. Let's next acknowledge what young readers need, which is to say the facts of then and now. You can already get that sort of thing in novels written for younger readers. Certainly Patricia McCormick is not writing down, making it easy, simplifying when she writes about the sex trade or the Cambodian war….And certainly I, writing novels for young adults, am not setting history down in burnished, skip-over-it slices.  Librarian Liz Burns, who blogs for School Library Journal wrote: In a nutshell, my response: There is nothing wrong, and actually much right, with writing age-appropriate nonfiction books for children and teens. When and how subject matter is introduced and discussed is, well, the reason fifth graders aren't sent to university classes (unless they're Doogie Howser, of course.) In her longer response Liz Burns drew the distinction between books for children under 13, and books for teenagers. She also pointed to what I see as the more fundamental and important issue—getting appropriate books to readers no matter what their age, and our lack of commitment to that end. Schools are increasing their purchasing of nonfiction at a time when the resources to do so have been reduced. Funding for books is decreased; and professional librarians, who evaluate and find books, have reduced hours, increased responsibilities, or have been eliminated all together. Perhaps this is all just a flap over a few sensational words in the news, but even so, it’s an opportunity to ask ourselves if we really mean it when we say we want kids to read more, and if they deserve quality books, and librarians to get the right book, at right time, into a child’s hands.  I can't close without sharing the Washington Post's words about PURE GRIT. Farrell doesn’t spare her young readers any grim details . . . She includes the challenges these women faced and the joy they felt on returning home. As awful as history can be, now might be the right time to introduce the next generation to this important period. --The Washington Post

0 Comments

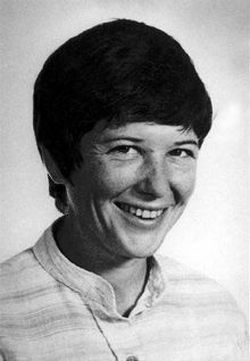

Fannie Sellins is back! I'm working on the final edits of her biography scheduled for release in 2016, nine years and many revisions after I began the project. Fannie Sellins entered my life via a Google search on American labor history back in 2007--In the Midst of Terror She went out to Her Work was one entry that turned up. Who could pass on that? Not me. The article by Mary Lou Hawse started like this: "Fannie Sellins was a labor organizer -- and from all accounts, she was an exceptional one. But she paid with her life." Suffice it to say, I was off like a bloodhound tracking scent and by the end of the day, I was determined to write a book about this woman.  Ita Ford Ita Ford She reminded me of Ita Ford, one of the Maryknoll sisters brutally murdered by national guardsmen in El Salvador in 1980.Both women shared a love for the poor, selfless courage, and a focus on people's everyday needs while working for systemic change. Ita chose to work in El Salvador, where a small minority controlled the vast majority of the country's wealth and most people lived in poverty. She was fully aware of the death squads raining violence on those who spoke out against the system, including the Catholic Archbishop of El Salvador Oscar Romero who was assassinated while saying Mass. Ita believed deeply in Romero's words, "one who is committed to the poor must risk the same fate as the poor. And in El Salvador we know what the fate of the poor signifies: to disappear, to be tortured, to be captive and to be found dead." In 1913-14, Fannie Sellins made her home among the destitute miners’ families in the nonunion coal fields of West Virginia. The United Mine Workers Journal called her an "Angel of Mercy," who went into the miners' homes, encouraging their wives and caring for the sick and dying. "Whenever there was a strike, with its inevitable suffering, Mrs. Sellins was found, caring for the women and children through the dark days of the struggle." Threatened with arrest for urging miners to join the union, Fannie said, “The only wrong that they can say I have done is to take shoes to the little children in Colliers who need shoes. And when I think of their little bare feet, blue with the cruel blasts of winter, it makes me determined that if it be wrong to put shoes upon those little feet, then I will continue to do wrong as long as I have hands and feet to crawl to Colliers.” When the miners’ union was crushed in West Virginia, Fannie moved to Pennsylvania’s Black Valley, they called it the Black Valley. The name sprang from the fighting between labor unions and mine owners. Fighting so fierce, they called it war. Labor war. In late summer 1919, miners struck Allegheny Coal and Coke in Brackenridge, PA. Fannie was warned to leave town if she valued her life. She stayed. She walked the picket lines with the men and rallied strikers to stick it out.  Women at Fannie Sellins Funeral, St. Peter’s Church, New Kensington PA Women at Fannie Sellins Funeral, St. Peter’s Church, New Kensington PA She tried to keep peace, while the two sides heckled each other and often came to blows. One afternoon an argument broke out between sheriff’s deputies and an unarmed miner. A crowd gathered, including Fannie, seeing deputies club, then shoot and kill the man. She shouted for the lawmen to stop. They turned on her, gunning her down as she tried to herd nearby children to safety. Ita and Fannie did not give their lives in some grand gesture of generosity and selflessness, they simply got up each morning and did the work that was before them. For Ita, it was driving people where they needed to go in the rocky hills of El Salvador, or delivering medicine and food. For Fannie, it was helping a poor woman in labor or encouraging workers to believe they deserved better. They stood with the poor and powerless with such integrity that those with power and wealth could not allow them to live. For more on the men who ordered Ita's death click here. For the rest of the story on Fannie, you'll have to wait for the book. :) |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|