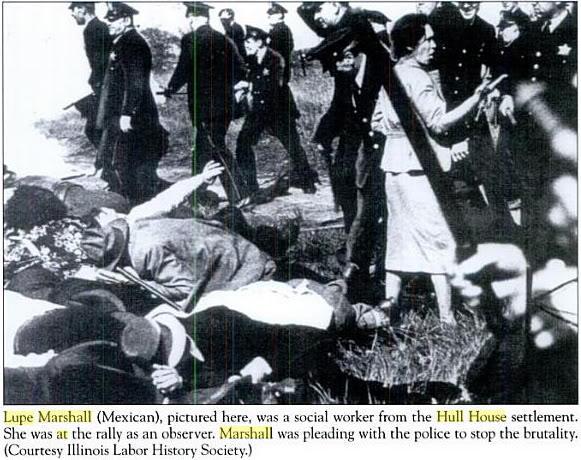

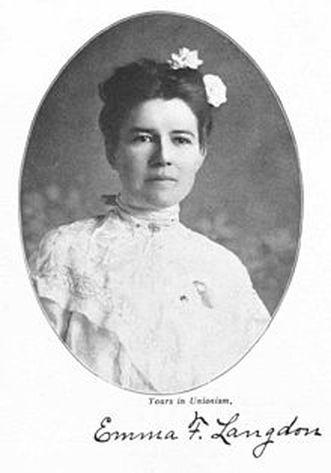

Sheriff's deputies charge women marching in support of strikers, Trinidad, CO, 1914. Sheriff's deputies charge women marching in support of strikers, Trinidad, CO, 1914. In writing about Fannie Sellins, I pulled an unknown heroine out of obscurity to offer today's young women a broader picture of their history. Along the way, I uncovered similar labor union women, whose bravery has likewise been forgotten. This week, I share some of their stories in honor of the birth day of Fannie Never Flinched, which is Tuesday, in case you missed it!  Photo courtesy Wayne State University, Eric Margolis Photo courtesy Wayne State University, Eric Margolis In this photo you see the grim faces of strikers outside a union hall in Walsenberg, Colorado after two strikers were shot dead by state police. But you'll never see the face of the woman who took charge of the strike after all the union leaders were arrested. She's described as a "Mexican mother", a "Indian half breed" and "Mrs. Felix Arrellano" whose husband had been injured in a mine accident. Though her name is lost to history, The Denver Morning Post recorded her words and deeds, telling how she led a crowd of women storming the jail, demanding to see their husbands and sons who'd been locked up, or transported across the state line under threat of death if they returned. "If we were asking for diamonds we wouldn't deserve them," this nameless woman began her fiery speech."But we are asking for bread."  Half a dozen strikers were shot dead and scores wounded before mine owners finally gave in and settled the strike, though they refused to recognize the union. Another labor union heroine is Emma Langdon, and we know her name because she set linotype at a union newspaper in the gold mining district of Cripple Creek, Colorado. During the Cripple Creek Strike in 1904, national guard troops arrested the staff of the Victor Daily Record. But they overlooked Emma, maybe because she was a woman. She sneaked into the newspaper office and working through the night, published the next morning's edition. Another brave woman tried to stop the violence of one of the bloodiest attacks in American Labor history. On Memorial day, 1937, a steelworkers strike turned deadly in southeast Chicago. Police opened fire on a crowd of men, women and children marching toward the front gate of Republic Steel. Ten workers were shot dead and thirty wounded. Lupe Marshall, a housewife and social worker was one of another fifty-five union sympathizers beaten in the melee of police clubs, tear gas and bullets. During and investigation by the U.S. Senate Committee on Education and Labor, Lupe described what happened that day. I evaded these policemen that were immediately in front of me . . . . I was aware that my head was bleeding. I noticed that my blouse was all stained with blood, and that sort of brought me to, and I started walking slowly toward the direction from which a policeman had just clubbed an individual, and this individual dragged himself a bit and tried to get up, when the policeman clubbed him again. He did that four times....I screamed at the policeman and said, “Don’t do that. Can’t you see he is terribly injured?” And at the moment I said that, somebody struck me from the back again and knocked me down. Before Lupe and other victims received medical help, one man died, his head in her lap. As often happened when strikes turned violent, police claimed they acted in self-defense and blamed the violence on communists and radicals.

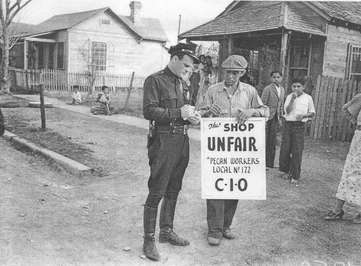

Some fifteen years later during the McCarthy era, Lupe Marshall was charged with communism and faced deportation under the McCarran-Walter Act of 1952. There is no evidence that she had done anything illegal or was a threat to national security, but she moved to Jamaica and never returned to the U.S.  Emma in San Antonio jail, courtesy Dolph Briscoe Center for American History Emma in San Antonio jail, courtesy Dolph Briscoe Center for American History Before Cesar Chavez and the grapes boycott there was Emma Tenayuca and the pecan strike. Emma was sixteen when she first went to jail, arrested for joining a labor strike by San Antonio cigar workers in 1932. Emma picked up her social activist ideas at her grandfather's knee, going with him to the La Plaza del Zacate, the center of activity for Mexican American families in West San Antonio. Children could get an ice cream. Jobless families might be hired to pick cotton or work in the beet fields. Stories went round. You could hear the latest news from Mexico read aloud, preaching from the bible and fiery political speeches.  Police cite union picket in pecan workers strike, San Antonio, TX 1938 Police cite union picket in pecan workers strike, San Antonio, TX 1938 Seeing police bully picketers during the cigar makers' strike, propelled Emma to keep working for the rights of the poor, a fight that would nearly cost her her life. She soon became well-known in San Antonio after leading several marches, demonstrations and sit-ins. Emma campaigned for a minimum wage, and took up the causes of unfair allotment of New Deal public works jobs, discriminatory removal of Mexican American families from WPA relief roles, and illegal deportations of U. S. citizens of Mexican descent. "I never thought in When some 12,000 pecan shellers walked off the job to protest a wage cut, they converged on a local park shouting "Emma! Emma!" and chose her to lead their strike. She was 21. Pecan-shelling was a major industry in the region and one of the lowest-paid in the country. Workers, mostly Hispanic women, typically earned between two and three dollars a week. Work areas were badly ventilated and poorly lit without indoor plumbing. San Antonio law enforcement met peaceful picketers swinging clubs, hurling tear gas canisters and making mass arrests. Seven hundred strikers were arrested one day, under orders from the chief of police who stated the strike was a "Red plot" to gain control of the West Side of San Antonio. At that point, the union removed Emma as an official leader of the strike, fearing her ties to the Communist Party would hurt the cause. The strike, one of the largest in the nation, continued for three months until pecan producers agreed to pay the minimum wage set by the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.  Emma Tenayuca stands on the steps of City Hall, San Antonio, 1938. Courtesy Institute of Texan Cultures Emma Tenayuca stands on the steps of City Hall, San Antonio, 1938. Courtesy Institute of Texan Cultures Emma Tenayuca was blacklisted for being a communist in the 1930s, and still today, she is not considered a heroine by some people for the same reason. Yet, she was deeply concerned about many of the same issues that trouble us today, the disparity between the rich and the poor, discrimination against people of color and fear of immigrants. Emma courageously went to jail a number of times for her beliefs, saying, "I never thought in terms of fear, I thought in terms of justice." Some months after the pecan strike settled, Emma planned to speak at a Communist Party meeting at the city's auditorium. A crowd of 5000 anti-communists gathered to protest and as they stormed the building with bricks and stones, police guided Emma to through a secret underground tunnel. The rioters, including members of the Ku Klux Klan went on to burn the city mayor in effigy for permitting Emma the right to free speech. Fearing she'd be lynched, Emma left for Houston and later California, unable to return to her hometown for twenty years. Writer Carmen Tafolla wrote of Emma: "La Pasionaria, we called her, because she was our passion, because she was our heart -- defendiendo a los pobres, speaking out at a time when neither Mexicans nor women were expected to speak at all."  The Nazis purposefully chose Jewish holy days for effect when introducing anti-Semitic policies in occupied-Poland. They toyed with people before moving on to genocide. When the Nazi's attacked Warsaw September, 1939, it didn't matter if you were Jewish or Catholic or atheist, everyone worked together for weeks, hoping to hold the city against the Germans. Photo courtesy Polish National Digital Archive https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4139293 The Polish Army understood that Yom Kippur was the most holy day of the year for Jews and excused them that day from the crucial work of digging defensive trenches. But German bombs had destroyed many synagogues and homes in Jewish neighborhoods so all able males, including children and old men rallied at the city’s barricades, praying the prayers for the Day of Atonement while they worked to protect their city, even as air attacks continued. From Irena's Children, Young Readers Edition, a year later, Oct. 12, 1940.  "Already there was tension. The Germans had forbidden all public worship and a number of Jews had decided they would defy the order. As many were rising from sleep, loudspeakers squawked outside their windows. Jewish leaders, the Judenräte, heard the news from city officials, but ordinary people, Irena’s friends, heard it blaring in the street. It was the most sweeping edict yet. Every Jew in Warsaw must move into one small section of the city. They had two weeks. There would be no exceptions." A long blast of the shofar marked nightfall and the close of Yom Kippur in Warsaw’s Jewish neighborhood. Panic gripped the Jewish community at news of the Nazi’s latest command. The Germans wasted none of their orderly methods on a system to help the nearly one in four Warsaw families ordered to pick up household and move. Photo below courtesy Library of Congress, European Jew blows Sabbath shofar, circa 1935 Before the Nazis invaded Poland, 375,000 Jews lived in the capital city, about 30% of Warsaw's total population. As German bombs fell and the Polish Army retreated, refugees flooded to Warsaw pushing the number of Jewish people eventually imprisoned in the ghetto to 450,000.

At the end of the war, only 11,500 Jews had survived. Twenty-five hundred of those were children rescued by Irena Sendler and her underground network. Read that story in Irena's Children. |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|