|

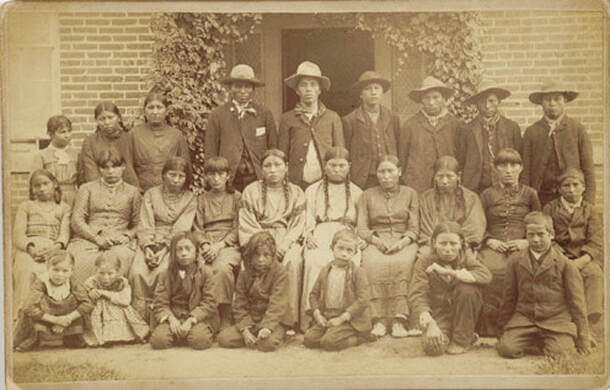

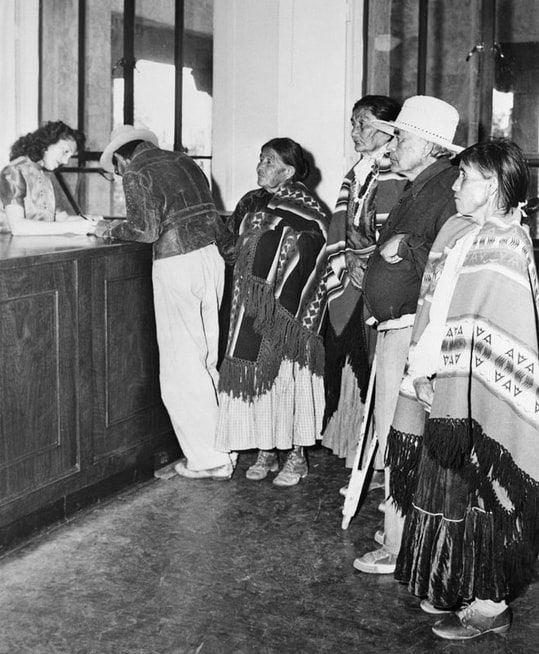

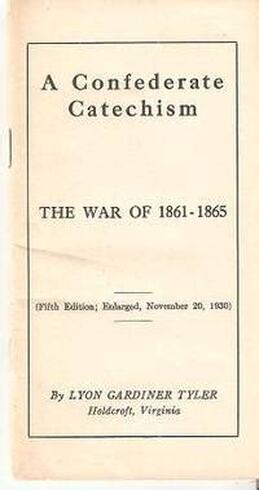

In the early 1900s, some American women campaigned for suffrage, picketed, went to jail... Other women formed a massive movement to erect monuments glorifying the Confederacy, re-write the history of the Civil War and indoctrinate children using a Confederate Catechism. (Link to catechism below.) These women wrote and controlled history textbooks in Alabama, Texas, Louisiana and other southern states for three generations. Textbooks that described a close friendship between "old massa" and slaves, picnics and barbeques thrown where slaves had a "great frolic," and stated how enslaved people sang as they worked in the fields, "the beat of the music and richness of their voices made work seem light." Is it any wonder the confederate flag means so much to so many people? That Robert E. Lee is such a vaunted hero? They learned it in catechism! (See video after feature story below) Today, Brandon Marie Miller, author of Robert E. Lee, the Man, the Soldier, the Myth, is here to help us separate fact from fiction. Welcome, Brandon! Breaking Down the Myths of Robert E. Lee Author Brandon Marie Miller Author Brandon Marie Miller I never thought my YA biography of Robert E. Lee would be so timely. But one way to fight racism and white supremacy is by accepting truths about our past. 150 years after his death, Lee remains in history’s spotlight. Some people today still claim Lee did not own slaves, he hated slavery, he favored emancipation, and he promoted reconciliation after the Civil War. Let’s take a closer look. Lee and Slavery “Slavery as an institution,” Lee wrote his wife in 1856, “is a moral & political evil in any country.” Sounds good, right? But a sentence down in this same letter Lee explains “I think it however a greater evil to the white than to the black race.” Lee believed God approved slavery as a means to civilize Black people. Even the “painful discipline” inflicted was “necessary for their instruction as a race.” For Lee, Black people were morally unfit for freedom and not as capable of learning as whites. Photo below: Selina Norris Gray, the enslaved housekeeper at Robert E. Lee's home, Arlington, shown with two of her daughters. (Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial.) He felt slavery was messy, though, an inefficient system forcing “unwilling hands to work.” He disliked having to feed, clothe, and house people he found lazy and ungrateful. Lee wrote his new bride about their household slaves, “you may do with them as you please…But do not trouble yourself about them, as they are not worth it.” After his father-in-law’s death, Lee inherited around 200 enslaved people. They were to be freed within five years. But Lee petitioned a court to keep these men, women, and children in bondage while he made his father-in-law’s plantations profitable. The enslaved sabotaged Lee’s efforts. They ran away, broke items, and stole things. Lee had people whipped or rid himself of troublemakers by hiring them out or sending slaves to Richmond to be “disposed of…to the best advantage.”  Although against secession, once war loomed, Robert Lee resigned the U. S. Army commission he’d held for nearly 35 years. Within days, he accepted a commission as major general of Virginia’s forces. Lee knew the Confederacy existed to protect slavery and the right to expand slavery into the western territories. He had resented the North’s attempts to block the spread of slavery into the west which threatened, he wrote, the “equal rights of our [Southern] citizens.” “The South…has been aggrieved by the acts of the North” he told his son, “... I feel the aggression.” Did Lee believe in emancipation for enslaved people? Lee believed in gradual emancipation which would only come when God decided, maybe not for thousands of years in the future. Lee did not free his family’s enslaved property until a court ordered him to obey his father-in-law’s will in 1862. Does that make him an emancipator? Lee did approve one method for freeing slaves. In January 1865, three months before he surrendered, Lee advocated using slaves to fight for the Confederate Army. However, across the trenches, tens of thousands of former slaves wore Union blue uniforms. Lee needed soldiers and proposed giving “our negroes” freedom upon enlisting and freedom for their families at the end of the war, though this came too late in the war to matter. Does this make Lee an emancipator? Did Lee work for reconciliation after the war? Lee urged fellow Southerners to “promote harmony and good feelings” as the quickest means to regain voting rights for white men and rebuild southern prosperity. After the war Lee served as president of Washington College where he implemented rigorous programs to educate and uplift young men of the South. But Lee’s words of reconciliation gave way to anger as the “evil legislation of Congress” granted civil rights to the former enslaved. Washington College students harassed African Americans, destroyed a Freedman’s Bureau school, and nearly lynched a man. The President's House that Lee designed and built at Washington College. (Special Collections Department, Washington and Lee University)  Lee disciplined a few ring leaders but never spoke out publicly against the violence toward African Americans sweeping the South. His response emphasized instead how students disturbed “the public peace, or bring discredit upon themselves or the institution to which they belong.” Lee rejected this new world where “the South is to be placed under the dominion of the negroes.” Publicly he claimed he wished the former enslaved well, but privately Lee wrote, “Remember, our material, social, and political interests are naturally with the whites.” In 1868 Lee signed a political statement known as the White Sulphur Springs Manifesto. The signers pledged to treat Blacks with “kindness and humanity,” while opposing any “laws which will place the political power of the country in the hands of the negro race.” This statement, and others, helped justify continued violence against African Americans for participating in the American political system.  How did the reality of Lee’s racism and white supremacy get turned around? In June of 1870 Lee wrote a cousin he hoped to shape “the opinion which posterity may form of the motives which governed the South in their late struggle.” He began reframing the war as a political quarrel-- the North strayed from the ideals of the Constitution while the South fought to maintain “those principles of American liberty.” He’d fought for state’s rights, not the cause of protecting slavery, Lee claimed. He disregarded the fact that the state’s rights insisted upon in 1860 and 1861 had been the right to own slaves and spread slavery into the west. In the decades after Lee’s death in October 1870, the handsome hero image of Lee grew to saint-like perfection. The ugliness of slavery could not tarnish this mythical man. Over time, the myth that he didn’t own slaves and supported emancipation became truth in the South and the North. Lee became a symbol of a righteous South. For many white Americans the soothing myth of Lee as a kind, honorable, Christian Gentleman, was more important than the economic suppression, voting suppression, and murder of African Americans. Groups like the United Confederate Veterans (founded 1889) and The United Daughters of the Confederacy (founded 1894), worked tirelessly to vindicate the Old South, intentionally rewriting history. The UDC distributed a booklet nation-wide to control what appeared in textbooks, shaping our Civil War memory for generations.  Among the reasons listed to condemn a book: “Reject a book that says the South fought to hold her slaves. Reject a book that speaks of the slaveholder of the South as cruel and unjust to his slaves. Reject a text book that glorifies Abraham Lincoln and vilifies Jefferson Davis….” Lee’s portrait graced thousands of Southern classrooms; many celebrated his birthday. Members of The Children of the Confederacy recited from A Confederate Catechism, first published in 1904. It included lessons like this one: “What did the South fight for? It fought to repel invasion and for self-government, just as the fathers of the American Revolution had done.” As Jim Crow laws stripped civil rights from African Americans and sharecropping became a new form of slavery, statues of Confederate heroes rose in cities across the South. Dedication ceremonies included parades, speeches, and hundreds of children arranged into “living” Confederate battle flags. The monuments reinforced white Southerners’ pride in the past, romanticized the Old South and slavery, and warned African Americans to keep to their place. I spent years researching and writing this book and have used Lee’s own words, and the words of his family and friends, to tell the story. I’m grateful ROBERT E. LEE, THE MAN, THE SOLDIER, THE MYTH was named a National Council of the Social Studies Notable Book and a Bank Street College Best Book of the Year. If you’d like to know more, order a copy from your favorite bookstore or online here... Thank you, Brandon! I'm so appreciative of you taking time to tell us about your new book, and to help us understand more about the roots of racial injustice in our nation and the concerted efforts to re-write history. Also thanks to author Claire Rudolf Murphy for alerting me to this video below about the women who helped distort the truth of the Civil War, construct a false legacy and indoctrinate children. Zitkala-Ša, also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, became a "Joan of Arc" figure who led her people in the arduous effort to gain citizenship and suffrage. You will not fine either of her names not chiseled into the monuments of history with the many white women who fought for the right to vote. But her story reads like a novel that you cannot put down. Photo below: (Original Caption) 2/1921-Among the prominent women who attended the meeting of the National Women's party in Washington was Mrs. Gerturde Bonnin, nee Princess Zitkala-Sa of the Sioux. Courtesy National Women’s Party.  The 19th Amendment ratified 100-years ago, August 18, 1920, granted American women the right to vote, but indigenous people were not considered Americans. The U.S. refused Native Americans birthright citizenship, and also allowed no process for them to become naturalized as immigrants could. Zitkala-Ša (Red Bird) fought for native citizenship, which was finally granted by Congress in 1924, four years after women gained the right to vote. But even as citizens, Indian women couldn't automatically vote, some were refused suffrage until 1962. Not a typo. 1962. Scroll down for more on that, but we'll get to it. First, Zitkala-Ša. This multi-talented woman was born on the Yankton Sioux Reservation in South Dakota in 1876 (the year of the Battle of Little Big Horn, known to Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass and historically as Custer's Last Stand). She was eight years old when Quaker missionaries came to the reservation to get children for their boarding school. Zitkala-Ša would later write that her years at White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute were "both a revelation and a misery." Check out this newspaper article heralding the success of the students at White's Institute. White's Institute, founded as an integrated school for all races had languished for twenty years, unable to attract boarding students, teachers and staff. Then in 1882, White's board of directors decided to contract with the U.S. government to educate native students. The school devoted itself to assimilating them into white society. The newspaper reported: Twenty seven Sioux children arrived for a three-year course of study. They were unkempt, ignorant and coarse, and true to their natural instincts were as shiftless. Below is a photo of the first class arriving at White's. Zitkala-Ša started at the school a year or two later. Photo courtesy: https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/photos-american-indians-whites-institute-wabash-indiana Stripped of her native clothing and forbidden to speak her native language, Zitkala-Ša ran and hid the day she was scheduled to get her hair cut. "Late in the morning, my friend Judewin gave me a terrible warning. Judewin knew a few words of English; and she had overheard the paleface woman talk about cutting our long, heavy hair. Our mothers had taught us that only unskilled warriors who were captured had their hair shingled [cut] by the enemy. Among our people, short hair was worn by mourners, and shingled [cut] hair by cowards!... I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids," Zitkala-Ša remembered later. "Then I lost my spirit" "We’d lost our hair and we’d lost our clothes; with the two we’d lost our identity as Indians." remembered another former boarding student Francis LaFlesche. "Greater punishment could hardly be devised.” The local newspaper reported: "Except in studies requiring close reasoning the progress made by the pupils after mastering the English language is as rapid as that of the average English student. They appear, however, unable to arrive at logical conclusions and read deductions intuitively. Rarely, indeed, do they betray any sign of homesickness…" Despite the indignities, punishment and being forced to pray as a Quaker, Zitkala-Ša discovered great joy in learning to read and write English and to play the violin. Photo below by Gertrude Kasebier, 1898. Smithsonian Institution, Public Domain  After several years at White's Zitkala-Ša went back to her home on the reservation, but discovered that she did not fit in there. She returned to the school and continued her education. At her graduation ceremony she gave a speech calling for women's right to vote. Earning a scholarship to Earlham College, she excelled in her liberal arts studies. At Earlham, Zitkala-Ša started her writing career, gathering Native American stories and translating them into English and Latin. She evolved the skills that would make her a powerful activist, once winning a speech contest in the the face of a big poster calling her a "squaw". Following Earlham, she studied violin at the New England Conservatory of Music, once playing before President William McKinley. While succeeding in white society, Zitkala-Ša remained anguished at her separation from Sioux culture. Hired at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania to teach music, she found herself face to face with students stripped of their Native identity as she had been. The rift inside her cracked wide when Carlisle sent her to Yankton to collected more students. She found the reservation swamped in poverty, her mother's home falling apart and white settlers violating Dakota lands in violation of federal treaties. By now, she was a published writer and her short stories published in Atlantic Monthly and Harper's portrayed the wisdom and generosity of her people, and belied the bigoted notions so commonly accepted by mainstream Americans. Her writing criticized Carlisle and other boarding schools for their assimilation practices. She was fired. Zitkala-Ša connected with other Native Americans capitalizing on their formal education and flawless English to advance the rights of Indian People. She helped establish the National Council of American Indians and committed herself to working for citizenship for Native Americans. They made huge progress in 1924 when an act of Congress granted full citizenship to all of the approximately 125,000 of 300,000 indigenous people living in the United States. But the parameters of those rights would be drawn by individual states where legislators and voters harbored stubborn prejudices. Native Americans registering to vote circa 1948. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images Arizona – home to part of the Navajo Nation and with the second-largest Native population in the country did not allow Native Americans to vote until the Supreme Court overruled the state's ban 1948. The State of Maine approved Native American Voting rights in 1953, with 25% of voters in opposition. Utah and New Mexico withheld the ballot box from Native Americans until 1962. Like African Americans, Natives suffered continued hurdles to voting until the1965 Civil Rights Act, and their voting rights remain under attack today. Many will run into trouble voting in the upcoming presidential election.  That's because in 2013, the Supreme Court extracted the teeth from the Civil Rights Act. In an Alabama case Shelby County vs Holder, the court declared the strong arm of the law unconstitutional, the section that required states with a history of racial bias in voting to get federal permission before enacting new voting laws. Since then a flurry of states and counties have changed voting regulations to constrain Native Americans and people of color from voting. Two months ago, the Native American Voting Rights Coalition released details of an extensive research project. Obstacles at Every Turn: Barriers to Political Participation Faced by Native American Voters lays bare the troubles Natives have in registering to vote, casting their votes and having their votes counted. It's a disgrace. Check these links for some of the latest state actions on Native American voting rights: Voter restrictions in North Dakota and historic voter rights legislation in Washington. Zitkala-Ša wrote stories and poetry, she was a teacher and a musician who raised her voice and worked for justice. Living and working on the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in Utah, Zitkala-Ša collaborated with a professor at Brigham Young University to compose The Sundance Opera, which premiered in 1913, the first Native American Opera ever performed. Often Zitkala-Ša has not been credited for the composition, though it's believed she wrote the libretto and songs of the opera, which was based on a sacred Sioux ritual that had been prohibited by the federal government. In this time of great division in the U.S. we truly need the spirit of Zitkala-Ša. She never denied the searing ache of two opposite ways of life, of two different modes of thinking. Somehow, she brought them together within herself and created great beauty, strength and hope. Sources: https://learninglab.si.edu/resources/view/48790#more-info https://www.nps.gov/people/zitkala-sa.htm https://build.headonwest.com/the-gifted-and-conflicted-life-of-lakotas-zitkala-sa/ |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|