|

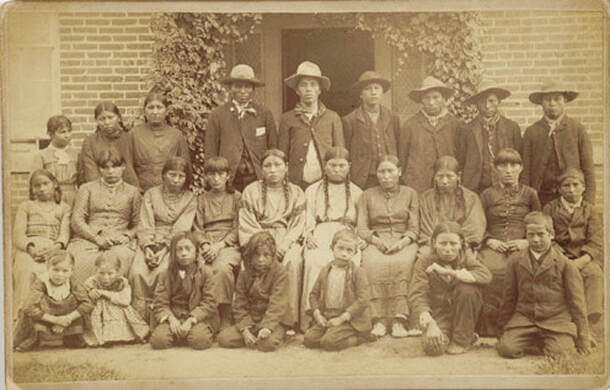

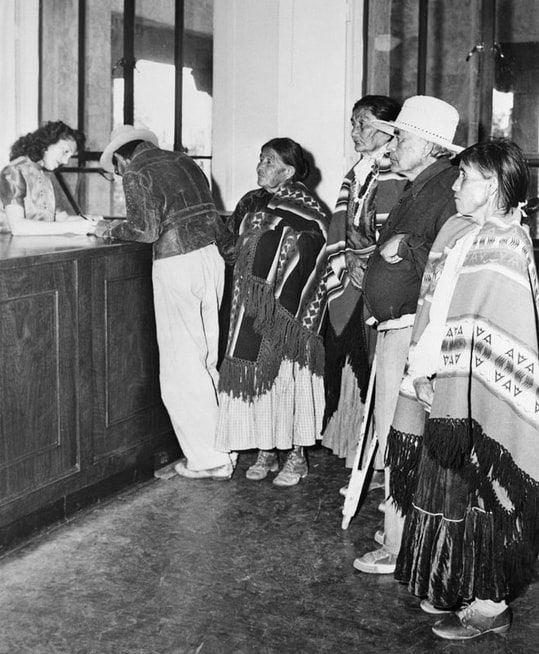

Zitkala-Ša, also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, became a "Joan of Arc" figure who led her people in the arduous effort to gain citizenship and suffrage. You will not fine either of her names not chiseled into the monuments of history with the many white women who fought for the right to vote. But her story reads like a novel that you cannot put down. Photo below: (Original Caption) 2/1921-Among the prominent women who attended the meeting of the National Women's party in Washington was Mrs. Gerturde Bonnin, nee Princess Zitkala-Sa of the Sioux. Courtesy National Women’s Party.  The 19th Amendment ratified 100-years ago, August 18, 1920, granted American women the right to vote, but indigenous people were not considered Americans. The U.S. refused Native Americans birthright citizenship, and also allowed no process for them to become naturalized as immigrants could. Zitkala-Ša (Red Bird) fought for native citizenship, which was finally granted by Congress in 1924, four years after women gained the right to vote. But even as citizens, Indian women couldn't automatically vote, some were refused suffrage until 1962. Not a typo. 1962. Scroll down for more on that, but we'll get to it. First, Zitkala-Ša. This multi-talented woman was born on the Yankton Sioux Reservation in South Dakota in 1876 (the year of the Battle of Little Big Horn, known to Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass and historically as Custer's Last Stand). She was eight years old when Quaker missionaries came to the reservation to get children for their boarding school. Zitkala-Ša would later write that her years at White's Indiana Manual Labor Institute were "both a revelation and a misery." Check out this newspaper article heralding the success of the students at White's Institute. White's Institute, founded as an integrated school for all races had languished for twenty years, unable to attract boarding students, teachers and staff. Then in 1882, White's board of directors decided to contract with the U.S. government to educate native students. The school devoted itself to assimilating them into white society. The newspaper reported: Twenty seven Sioux children arrived for a three-year course of study. They were unkempt, ignorant and coarse, and true to their natural instincts were as shiftless. Below is a photo of the first class arriving at White's. Zitkala-Ša started at the school a year or two later. Photo courtesy: https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/photos-american-indians-whites-institute-wabash-indiana Stripped of her native clothing and forbidden to speak her native language, Zitkala-Ša ran and hid the day she was scheduled to get her hair cut. "Late in the morning, my friend Judewin gave me a terrible warning. Judewin knew a few words of English; and she had overheard the paleface woman talk about cutting our long, heavy hair. Our mothers had taught us that only unskilled warriors who were captured had their hair shingled [cut] by the enemy. Among our people, short hair was worn by mourners, and shingled [cut] hair by cowards!... I cried aloud, shaking my head all the while until I felt the cold blades of the scissors against my neck, and heard them gnaw off one of my thick braids," Zitkala-Ša remembered later. "Then I lost my spirit" "We’d lost our hair and we’d lost our clothes; with the two we’d lost our identity as Indians." remembered another former boarding student Francis LaFlesche. "Greater punishment could hardly be devised.” The local newspaper reported: "Except in studies requiring close reasoning the progress made by the pupils after mastering the English language is as rapid as that of the average English student. They appear, however, unable to arrive at logical conclusions and read deductions intuitively. Rarely, indeed, do they betray any sign of homesickness…" Despite the indignities, punishment and being forced to pray as a Quaker, Zitkala-Ša discovered great joy in learning to read and write English and to play the violin. Photo below by Gertrude Kasebier, 1898. Smithsonian Institution, Public Domain  After several years at White's Zitkala-Ša went back to her home on the reservation, but discovered that she did not fit in there. She returned to the school and continued her education. At her graduation ceremony she gave a speech calling for women's right to vote. Earning a scholarship to Earlham College, she excelled in her liberal arts studies. At Earlham, Zitkala-Ša started her writing career, gathering Native American stories and translating them into English and Latin. She evolved the skills that would make her a powerful activist, once winning a speech contest in the the face of a big poster calling her a "squaw". Following Earlham, she studied violin at the New England Conservatory of Music, once playing before President William McKinley. While succeeding in white society, Zitkala-Ša remained anguished at her separation from Sioux culture. Hired at Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania to teach music, she found herself face to face with students stripped of their Native identity as she had been. The rift inside her cracked wide when Carlisle sent her to Yankton to collected more students. She found the reservation swamped in poverty, her mother's home falling apart and white settlers violating Dakota lands in violation of federal treaties. By now, she was a published writer and her short stories published in Atlantic Monthly and Harper's portrayed the wisdom and generosity of her people, and belied the bigoted notions so commonly accepted by mainstream Americans. Her writing criticized Carlisle and other boarding schools for their assimilation practices. She was fired. Zitkala-Ša connected with other Native Americans capitalizing on their formal education and flawless English to advance the rights of Indian People. She helped establish the National Council of American Indians and committed herself to working for citizenship for Native Americans. They made huge progress in 1924 when an act of Congress granted full citizenship to all of the approximately 125,000 of 300,000 indigenous people living in the United States. But the parameters of those rights would be drawn by individual states where legislators and voters harbored stubborn prejudices. Native Americans registering to vote circa 1948. Bettmann Archive/Getty Images Arizona – home to part of the Navajo Nation and with the second-largest Native population in the country did not allow Native Americans to vote until the Supreme Court overruled the state's ban 1948. The State of Maine approved Native American Voting rights in 1953, with 25% of voters in opposition. Utah and New Mexico withheld the ballot box from Native Americans until 1962. Like African Americans, Natives suffered continued hurdles to voting until the1965 Civil Rights Act, and their voting rights remain under attack today. Many will run into trouble voting in the upcoming presidential election.  That's because in 2013, the Supreme Court extracted the teeth from the Civil Rights Act. In an Alabama case Shelby County vs Holder, the court declared the strong arm of the law unconstitutional, the section that required states with a history of racial bias in voting to get federal permission before enacting new voting laws. Since then a flurry of states and counties have changed voting regulations to constrain Native Americans and people of color from voting. Two months ago, the Native American Voting Rights Coalition released details of an extensive research project. Obstacles at Every Turn: Barriers to Political Participation Faced by Native American Voters lays bare the troubles Natives have in registering to vote, casting their votes and having their votes counted. It's a disgrace. Check these links for some of the latest state actions on Native American voting rights: Voter restrictions in North Dakota and historic voter rights legislation in Washington. Zitkala-Ša wrote stories and poetry, she was a teacher and a musician who raised her voice and worked for justice. Living and working on the Uintah-Ouray Reservation in Utah, Zitkala-Ša collaborated with a professor at Brigham Young University to compose The Sundance Opera, which premiered in 1913, the first Native American Opera ever performed. Often Zitkala-Ša has not been credited for the composition, though it's believed she wrote the libretto and songs of the opera, which was based on a sacred Sioux ritual that had been prohibited by the federal government. In this time of great division in the U.S. we truly need the spirit of Zitkala-Ša. She never denied the searing ache of two opposite ways of life, of two different modes of thinking. Somehow, she brought them together within herself and created great beauty, strength and hope. Sources: https://learninglab.si.edu/resources/view/48790#more-info https://www.nps.gov/people/zitkala-sa.htm https://build.headonwest.com/the-gifted-and-conflicted-life-of-lakotas-zitkala-sa/ Comments are closed.

|

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|