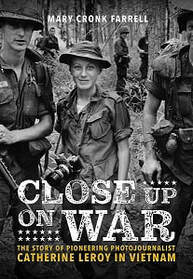

Last week I revealed the cover of my new book! Close Up on War: The Story of Pioneering Photojournalist Catherine Leroy in Vietnam is scheduled for release in early 2021. But it is available now for pre-order. Catherine Leroy spent most of her time in Vietnam in the field with U.S. troops. She rarely saw American women, even female journalists who were there at the same time. Plenty of military and civilian women went to Vietnam War during the war, but their service and sacrifice was not always appreciated. This past week marked the anniversary of one of the most crucial moments in American civil rights history. February 7, 1942, African Americans launched the Double V Campaign. It started with one man's question. "Should I sacrifice my life to live half American?" And it burgeoned into a force for equal employment opportunity for blacks during World War II, and laid a foundation for the civil rights marches in the 1960s.

|

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|