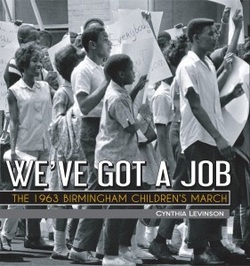

Elizabeth L. Gardner in a B-26 Marauder Elizabeth L. Gardner in a B-26 Marauder Like the WWII POW nurses I wrote about in PURE GRIT, the nearly two-thousand Women's Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) did not receive formal recognition for their courageous wartime service while they were alive. It took nearly 70-years and an act of Congress to get them a medal and formal thanks from the U.S. government. In 1942 when America's pilots were desperately needed in combat zones, there were not enough men to cover the bases at home. Up stepped 25-thousand young women pilots, eager to take to the skies and serve their country. Less than 2000 were accepted. "Here I was, a girl of 22, given a million-dollar airplane and told, "Go fly!" One said. They were not trained for combat, but flew fighter planes, bombers and every other kind of aircraft the U.S. Army had in World War II. The daring young WASPs not only transported cargo and flew planes from the factories to training bases and points of embarkation. They towed targets for live anti-aircraft artillery practice and simulated strafing missions.  The WASPs' story is told in the newly re-issued YANKEE DOODLE GALS, by Amy Nathan. She explains: Some were teenagers, right out of high school or just starting college. Others were teachers, librarians, flight instructors, or offices workers. They stopped what they were doing for the chance to fly fantastic planes and help their country win the war. These 1,102 women weren't allowed to fly in combat, but for two glorious years they put their lives on the line every day flying important, and often risky, stateside missions. They flew well and proved that a woman's place could very well be inside a military cockpit. In 1944 the war was going better for the U.S. and the Army decided it didn't need the women anymore and disbanded the program. Though the women flew dangerous missions for two years and 38 of the pilots died in accidents, they were never considered official members of the military. All records of their service were classified and sealed for 35-years. Little remembered of the women pilots' contribution to the war effort.  Finally in 2009, President Barack Obama and the U.S. Congress awarded the WASPs the Congressional Gold Medal. Three of the roughly 300 surviving pilots were there for the honor. During the ceremony President Obama said, "The Women Airforce Service Pilots courageously answered their country's call in a time of need while blazing a trail for the brave women who have given and continue to give so much in service to this nation since. Every American should be grateful for their service, and I am honored to sign this bill to finally give them some of the hard-earned recognition they deserve."  As many of you know it's been a rough week saying good-bye to my brother-in-law Javier. When you lose someone you love, you wonder how the world can just go on like it does. The rain still falls, cars go by, people haggle over the last piece of bacon. The gift of grieving is the compassion that comes with the realization that it's not my grief. It's our grief. In every small town and big city, someone's heart is breaking over the loss of a loved one. In every language spoken on earth people cry out in sorrow. Grief is born of love. Can we let our hearts be tender to its touch?  Everyday life is full of contradictions, situations where opposites are true at the same time. Practicing our ability to hold opposing truths builds resilience and lies at the core of a full and healthy life. After Javier's accident and traumatic brain injury, my sister Virginia lived with contradiction for seven-and-a-half weeks. She held hope and belief that her husband would recover, and she knew it was possible he wouldn't survive. Virginia cried in anguish, prayed with faith and she also laughed with joy. The staff at the hospital loved her. (As do we all) They continually spoke of her courage, her warmth, and her commitment to Javier. In between helping with Javier's therapy, she crocheted scarves for other patients! She attuned to joy in the midst of deep sorrow.  The joy of one last time on Daddy's 'dozer The joy of one last time on Daddy's 'dozer Virginia also juggled the contradictions innate between the needs of her husband and the needs of her young children. I love to see her smile and talk about her children. She told me a story about her five-year-old who said, "When Daddy comes home, I'm going to teach him his numbers and colors. Ten plus ten is twenty. Daddy's brain doesn't know that. But mine does." Virginia's practice of holding both joy and sorrow has strengthened her for the days of grief to come. This ability to hold and feel the opposites of joy and sorrow is critical to resilience. To cling only to sorrow, even though sorrow is true, leads to depression and/or bitterness. To cling solely to joy and not acknowledge the depths of pain and loss leads to numbness. Most days, we will not deal with the extremes that Virginia faces. On the periphery of her story, I have practiced being present to her and to my own grief, while at the same time celebrating the launch of PURE GRIT and my joy in work well done. Grasping such contradictions helped the American WWII nurses survive combat and prison camp. In the midst of danger, fear and death, cracking jokes was one way the women stayed centered. For instance, when nurses couldn't bring themselves to eat due to anxiety during the air raids, one joked that if hit, their chances of survival would be better on an empty stomach. After nearly three years in prison camp, the nurses continued to find humor in their situation to help keep their spirits up. Despite the hardships they suffered, the women grasped any excuse to celebrate. Army Nurses Rita Palmer said later, "The birthdays and anniversaries of the members of each one's family far away in the United States or some country were duly feted with a special tablecloth and a cake.” They continued to celebrate when they no longer had ingredients to make a cake. In late 1944, as many as five people were dying each day of starvation related ailments in Santo Tomas Internment Camp. The nurses were as sick as their patients. Army Nurse Frances Nash was so weak, her legs swollen with beriberi that she could hardly walk to the hospital. She wrote in her diary, “We had stood more than I had ever thought the human body and mind could endure.” She also wrote, “There was nothing beautiful in our lives except the sunsets and the moonlight.” Frances saw beauty in the midst of unimaginable suffering. If we open ourselves to what is true moment by moment, we will experience contradiction. Embracing the contradictions builds resilience and invites the fullness of life to flow through us. I'd love to know, what's your experience with these difficult contradictions in life and how we give them their due?  Audrey Faye Hendricks Audrey Faye Hendricks On Thursday morning, May 2, 1963, nine-year-old Audrey Faye Hendricks woke up with freedom on her mind. But, before she could be free, there was something important she had to do. "I want to go to jail," Audrey had told her mother. Since Mr. and Mrs. Hendricks thought that was a good idea, they helped her get ready. Her father had even bought her a new game she'd been eyeing. Audrey imagined that it would entertain her if she got bored during her week on a cell block. That morning, her mother took her to Center Street Elementary so she could tell her third-grade teacher why she'd be absent. Mrs. Wills cried. Audrey knew she was proud of her. She also hugged all four grandparents goodbye. One of her grandmothers assured her, "You'll be fine." Then Audrey's parents drove her to the church to get arrested. That's the first page of WE'VE GOT A JOB: THE 1963 BIRMINGHAM CHILDREN'S MARCH, by Cynthia Levinson. Hooked? I was. Cynthia graciously agreed to share something of what she learned about courage in the process of writing the book. Welcome, Cynthia.  Inevitably, a child asks me during a school visit, “So, would you do it?” I can tell by the group’s eager expressions that they want me to shout, “Absolutely!” They know they would do it. Invariably, however, I have to answer, “I wish I could say, ‘Yes.’ But I’m too cowardly.” Their new expressions tell me they’re disappointed. After all, why would their school invite an author who’s a wimp, especially when the story she’s just told them focuses on thousands of courageous children? As a result, I’ve been tempted to alter my response. However, not only must I be honest but also I’ve begun to realize that, paradoxically, their disappointment is part of why I’m there. When Mary Cronk Farrell asked me to write about how the subjects of my book, We’ve Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children’s March, affected me, I knew the topic would be complex. Through the experiences of four specific young people, the book tells the story of how 3000 to 4000 black school children desegregated Birmingham, Alabama—the city that Dr. King considered the most violently racist in the country. It was certainly the most thoroughly segregated, with laws and customs decreeing that “Negro and white people are not to play together,” that a seven-foot wall must separate blacks and whites in restaurants, that separate ambulances should carry sick people to separate hospitals.  Author Cynthia Levinson Author Cynthia Levinson Some black ministers and others tried for years to desegregate the town. But a racist police commissioner, named “Bull” Connor, who ignored bombs tossed at the homes and churches of civil rights activists, defeated them. Instead, children took the lead that May. They protested, picketed, sat-in at lunch counters, and, above all, marched. Even when the commissioner attacked them with snarling German shepherds and powerful water canons, the children held hands and kept marching. They also sang, prayed, were arrested en masse, spent days and nights in packed jails—and did it all peacefully. Two months later, the commissioner was defeated, and Birmingham rescinded its onerous and despicable segregation codes. So, when I tell school children today about the brave youngsters in Birmingham, they want to know if I would march, too. Would I sing and pray? Would I face dogs, hoses, and jail? The reason that I know, unfortunately, that I would not is that I did not. In May 1963, I was an eighteen-year-old high school senior in Columbus, Ohio. In fairness, not a single white person joined the black children during their protests in Birmingham so it’s not completely surprising that I didn’t fly down there. (Some white clergymen and the folk singer Joan Baez did, however.) Nevertheless, to the extent that I paid attention to the news, I was bewildered by what was happening down there. Worse, I hardly paid attention at all. In fact, although I knew about the dogs and the hoses, I didn’t know that it was children who took responsibility for desegregating their city until decades later. Furthermore, although later I did participate in a few protests about political issues I cared about, I chose tame ones where no one was going to get hurt. Because we know how events in the past have turned out, history in hindsight looks inevitable. Young people today could believe that the children of Birmingham weren’t in any real danger. Beforehand, however, Dr. King was so worried that someone might get hurt or killed that he opposed their actions. Sharing my own embarrassing past with them, I think, makes the threats more real. These were truly dangerous times. Courage, I hope they learn, does not entail ignoring the dangers but, rather, paying attention to them—and then making a decision about whether or not to proceed. Courage, I’ve learned, is not casual. Courage requires a cause. And, courage draws strength from cooperation. Thank you, Cynthia, for sharing your thoughts here. I'm moved by your honesty. We can all stand to look more closely at what's happening in the life around us and how we respond. I know your book will inspire many of us to do that. Click here for more on WE'VE GOT A JOB.

Over at her blog READ LIKE A WRITER, a Teaching Blog, Author Christine Kohler offers a look at how the stories of the World War II POW nurses were almost lost forever. In 1945, when the women arrived home after their three years as POW’s in the Philippines, their superiors had them sign statements agreeing not to speak of the atrocities they had seen. “They treated it as if it was a stigma,” said Lieutenant Colonel Hattie R. Brantley. A good number of the seventy-eight POW nurses had died before there was any effort to preserve their stories. Read more... And check out Christine's novel NO SURRENDER SOLIDER, a story encompassing the experiences of a WWII soldier, a Vietnam soldier and the boy that links the two. |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|