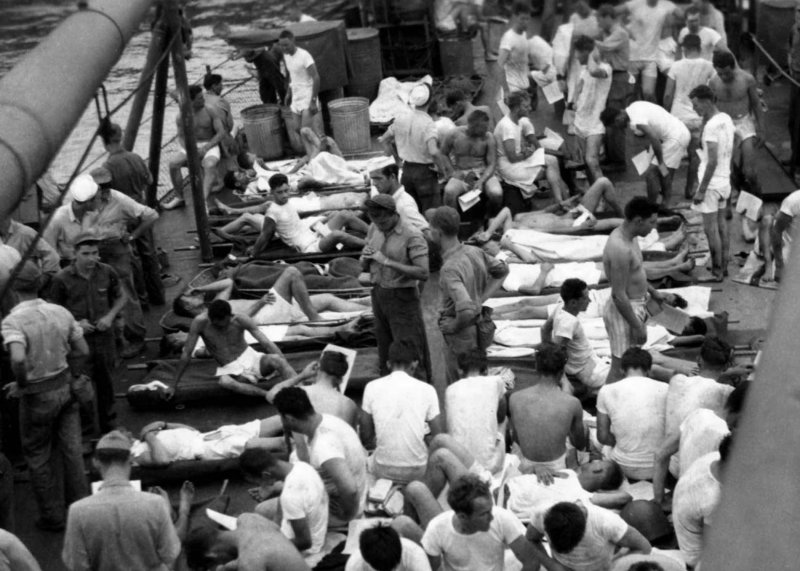

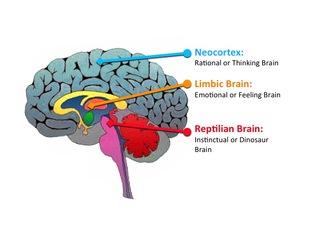

GABE ~ June 1996-April 2008 GABE ~ June 1996-April 2008 It was nearing midnight six years ago today when I got the phone call. You know the one. The one you never, ever want to receive. I’d been out celebrating with a friend whose new book had just came out, and had just settled into bed, ready to drift off to sleep. “Gabe’s not doing well,” she said. The tremble in her voice told me this was the worst kind of news. Gabe was in the hospital, but he’d been in before, and I’d never thought for one second that his life was in danger. Gabe was the eleven-year-old son of a very close friend. The family lived directly across the street from our house and I’d known Gabe since he was born. When I got off the phone my heart was beating so hard and fast, it seemed it would bust right out of my chest. My thoughts were completely incoherent. I knew I should get dressed and go to the hospital. But for a few moments I couldn’t even think how to put on a pair of pants. I dedicated my book PURE GRIT to Gabe because of the courage he demonstrated living with epilepsy. For several years, his seizures were controlled by medication.  But they grew worse and occasionally, the medication didn't work. Gabe loved basketball, and he would take to the floor with his team, even though he knew he might have a seizure on the court at any time. He didn't have grand mal seizures, but he would lose consciousness momentarily, freeze when all the other players ran down the court. His arm would stiffen out to the side. It might seem a small thing, but it's a huge risk to a child with epilepsy. It would have been easier to not to play, not to take the chance you might look strange in front of your friends and a whole gym full of strangers. Over time, stronger and stronger meds helped less and less. Doctors urged Gabe's parents to consider surgery to excise a part of his brain where the seizures originated. Brain surgery is always high risk. Anything might go wrong, but even a successful surgery could compromise Gabe's motor skills. He was a natural athlete and loved soccer, as well as basketball. Gabe's courage was often invisible. And it's hard to put into words. You would have had to live with him day in and day out to understand the courage it took for him to go to school when the meds made him drowsy, for him dribble a ball down the court when he'd had five seizures his last game. To see his strength, you would have had to be there when he went in to the hospital to have his brain mapped with electrodes. You would have had to see Gabe's face as he was wheeled away from his mom and dad and into surgery where the doctors would cut into his brain to understand that kind of courage. I mostly heard about it from his mom.  Every night, she had the task of asking him how many seizures he had that day and recording the number, if it hadn't been too many to count. Gabe had a hilarious sense of humor. He had bright blue eyes and a sweet, sometimes goofy smile. He used to shoot baskets at the hoop on the street for hours. He loved to watch LaBron James play ball.  Everyone was so excited the night he came home from that surgery, head shaved with a row of stitches across his scalp. Smiling. It was a year later when it became clear the surgery hadn't ended the seizures. One day Gabe had so many, he was hospitalized and doctors put him into a coma to stop them. It was a tragic fluke that Gabe suffered an allergic reaction to the Propofol they used to knock him out. His doctors had never seen it happen before. I doubt there's a parent alive who has not wondered how they would go on living if their child died. I never want to find out, but I have witnessed it now. After Gabe died, I learned the profound journey it can be to closely accompany a mother through such a loss. To witness such indescribable pain moment to moment, hour to hour, day to day, and year to year as it gives way ever so gradually to healing, is to witness a miracle of courage.  And so I dedicated PURE GRIT, not only to Gabe, but to his mother Cheryl. It's a small way to honor them and give thanks for how they have inspired me and enriched my life. The story of the USS Indianapolis was not pretty. Sunk by the Japanese at the close of WWII, only a quarter of her crew survived. Her captain was court-martialed and killed himself, possibly to escape the shame. Then in 1997, a sixth grader, Hunter Scott, interviewed survivors of the disaster for the school history fair. He thought they were heroes and that their captain got a bum deal. His project won the school fair, the country fair and then lost the state fair to a rock collection. But the boy believed in his project and continued his research, as well as his efforts to tell the true story of USS Indianapolis. The historical relevance of the ship was assured because of its secret mission, transporting the atomic bomb to the Mariana Islands in prep for the bombing of Hiroshima. As it turns out, that is but a footnote in the nearly unbelievable tale of this ship and men who sailed aboard her.  I learned about it in the book Left for Dead: A Young Man’s Search for Justice for the USS Indianapolis by Pete Nelson. The book combines the story of the survivors of the U.S. Navy's worst loss of life on a single ship with the story of Hunter Scott crusade to bring them the honor they deserved. After delivering the bomb, the Indianapolis set a leisurely course to the Philippines for some gunnery practice. The Indy was a cruiser, without the heavy armor of a battleship. At this point in the war, most of the fighting had moved to the far eastern Pacific closer to Japan, so the ship sailed without an escort. Though Japanese submarines had been sited earlier on the route, that information was classified and Captain Charles B. McVay wasn’t told.  Captain Charles B. McVay Captain Charles B. McVay It late July, a mere 12-degrees from the equator, as the ship sailed through the muggy heat, air-ducts, water-tight doors and hatches were opened to cool the lower decks. Still, many sailors carried their blankets topside and found a space to catch the breeze and get some sleep. Shortly before midnight on July 29, a Japanese submarine surfaced, and the captain, looking through his binoculars saw a black dot on the horizon. He thought it was fate, for as he watched, the moon come out of the clouds right behind the ship. Silhouetted on the vast dark ocean, the Indianapolis sailed straight toward him. He gave the order to dive, and then to fire. At 12:02 the first torpedo hit, ripping off the front starboard corner of the Indianapolis and igniting a tank of highly volatile aviation fuel. Seconds later, two more explosions rocked the ship. Bulkheads collapsed, the ship took on water and the engines drove the Indy down. It took only twelve minutes to sink. About 300 men died outright or went down with the ship; 880 were thrown into the sea. They huddled together in groups and tried to stay afloat in the oil-slick, shark-infested waters. Some were burned or otherwise injured; many had no life-jackets. The worst-off got to rest in life rafts, safe from the sharks. But there had only been time to cut loose a few of the rafts and there were too few survival provisions for the number of men in the water. One of the radio operators encouraged those around him, telling how he had sent out the SOS and their location. They must simply hang on until rescuers arrived. Nelson goes into detail about the horrors the men faced as they waited. The burned and bleeding, those with broken limbs and dazed from concussions were the first to die. Daylight brought sunburn and thirst and no rescue. The second day brought dehydration, hunger and nasty disputes. The third day brought hallucinations, and loss of the will to live. Every day the sharks came. They swam in circles around the groups of men. Without warning a man would scream, then disappear into the deep. Men went out of their minds. The United States Navy did not even know the Indianapolis was missing. It would be more than 50-years before the Navy discovered that the SOS message had been received by four different people. Hunter Scott discovered that in each case, it had been ignored. On the fourth day after the ship sank, survivors were sighted by chance, and planes and boats headed to the area to save them. The last of the 317 men alive was picked out of the ocean on the fifth day.  Survivors arriving on Guam after rescue. Survivors arriving on Guam after rescue. The Navy needed a scapegoat for this disaster and court-martialed the captain for not ordering a zig-zag course to avoid enemy torpedoes. The surviving men knew their captain was not to blame, and tried in vain for years to clear his name. Then in 1997, 11-year-old Hunter Scott heard Indianapolis disaster mentioned in the movie Jaws and decided to interview survivors for his history fair project. That set him on a course of friendship with the men and finally the exoneration of Captain McVay. I recommend this book because it's an important story that honors the survivors of the USS Indianapolis.There are recommend this book for two things the author does very well. One is the way he describes the science of how the human body reacts when deprived of drinking water while suspended in salt water. The second is his explanation of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as it was suffered by the survivors of the Indianapolis, and how, when in 1960, the men began to gather and talk about what had happened they began to heal. That healing was also helped in 2001 when, after Hunter Scott took their case to Congress, the crew of the Indianapolis were finally awarded a Navy Unit Citation.  Graphic from dangerandplay.com Graphic from dangerandplay.com I click open my novel to start revising and my heartbeat goes-- fight-or-flight, fight-or-flight, fight-o-flight! I jump up and go to the kitchen to microwave my cup off coffee. Even though it hasn’t cooled. In the moment of facing the page, I am like a mouse bolting from the swoop of a hawk. My amygdala (reptilian brain) fires a message to my sympathetic nervous system telling it that my body is in acute danger. This message is so commanding, I jump up and leave the room. I wrote about this fear a few months ago when I asked the question: What would you do, if you weren’t afraid. I’m exploring it more deeply today and asking: Why does part of my brain think revising a novel is a threat to my life? And what the heck am I going to do about it? First, I’m going to remind myself it’s not me. Fear happens to everyone. Sometimes I think the difference between what we want and what we're afraid of is about the width of an eyelash. ― Jay McInerney What I want is risk. What I fear is failing. What I want is fresh air, currents, and mountains. What I’m afraid of is heights, drowning, and change. – Lakin Easterling Fear of failure is part of the human condition, so I accept it. But acceptance isn’t standing on the doorstep, neither in nor out. Stepping into fear is crossing the threshold between the conscious and unconscious mind. When I feel my heart going fight or flight- fight or flight- fight or flight, acceptance means taking a deep breath and sitting still. Not scampering to the kitchen and not forcing myself to get started on that revision no matter what it takes. Sitting still, breathing deep, feeling fear. Feeling my rapid heart beat, feeling my quickened breath, feeling the nerve endings in my skin waking up. Letting the fear rise. Listening to what it’s trying to tell me. This what’s called getting to know yourself. In decades past, this was woo-woo, some silly sh%t therapist’s would tell you to do. In this decade it’s imperative. It’s imperative because if we don’t listen to the fear and learn, we will act on it. Everybody knows we humans don’t make good decisions with our amygdala.  We need to act under the power of our prefrontal cortex deeply engaged with our heart. Sitting still and getting to know our fear gives our frontal lobe time to overrule our flight or flight, reptilian brain. Don’t worry, it will still work if you’re about to be hit by a car. When we get familiar with our fear, we begin to realize that most of it is a lie. We’re afraid of things that might happen. Afraid of things we imagine. Afraid of things we can do absolutely nothing about. That’s when our heart opens. Sitting still with an open heart, using our prefrontal cortex our actions will be wise. When I feel my heartbeat speed up, and my breath quicken, I don’t say to myself, Mary, don’t be silly, revising a novel will not kill you. Rather, I see it as an opportunity to learn something about myself and to open my heart. I take it as an opportunity to practice acting from a place of wisdom. Make sense? A bunch of hoo-rah? Let me know what you think. |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|