|

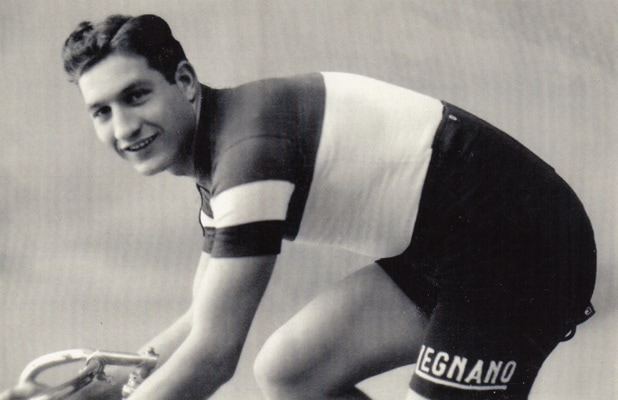

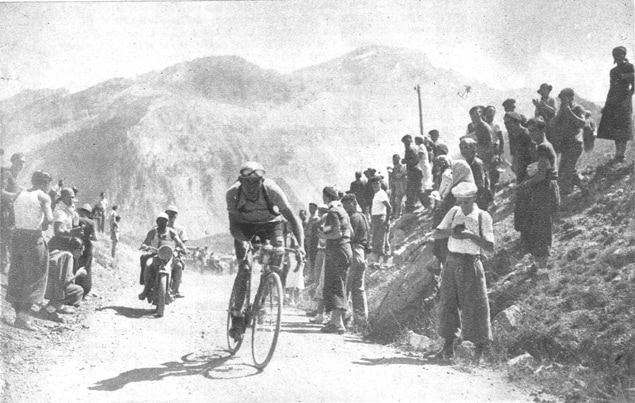

First day of summer, I dragged out my bicycle, my wonderful husband pumped up the flat tires, and I vowed to start riding it more and driving the car less. To inspire myself, I'm writing the story of Gino Bartali, one of the greatest cyclists of all time and a genuine hero. “Good is something you do, not something you talk about. Some medals are pinned to your soul, not to your jacket.” So said this two-time winner of the Tour de France. Above, Gino Bartali in 1936. In between his cycling victories, Bartali helped save some 800 Jews from the Nazis.  Gino Bartali grew from humble beginnings in rural Tuscany, his father a day laborer, his mother a lace maker. At age 11 he rode a bicycle to school in Florence from his village Ponte a Ema. Wheeling through the Tuscany hills, Gino developed a love for cycling, and a heart for tackling mountains. He won his first race at the age of 17, and at 24, rode to victory in the 1938 Tour de France, gaining international acclaim. Back in Italy, Benito Mussolini wanted to claim Bartali's victory as proof Italians were part of the master race, but in a risky move, Gino refused to go along with the fascist dictator. When World War II sidetracked Gino's cycling career, he found an even more valuable way to use his bike. In 1943, Germany occupied Italy and the Nazis started shipping Italian Jews to concentration camps. Bartali agreed to aid the Italian Resistance as a courier. Under the guise of long training rides and wearing an Italian racing jersey, Bartali risked his life transporting photographs and counterfeit documents in the hollow frame and handlebars of his bicycle. The photos and documents provided Italian Jews with false identity cards to protect them from the Nazis. People caught helping Jews evade capture were often executed immediately.  Bartali saved a friend Giacomo Goldenberg and his family by providing food and hiding them in an apartment he owned in Florence. Without his help, the family would most probably have died in the Holocaust. At left, the Goldenberg family--Elvira and Giacomo with their son Giorgio and their daughter Tea. In July 1944, Bartali was arrested and interrogated at Villa Triste in Florence, where local Fascist officials questioned and tortured prisoners. Fortunately, one of the interrogators had known Bartali before the war and convinced the others he should be let go. When the war was over, Gino went back to racing, racking up a third career victory in the Giro d'Italia in 1946, shown above. Then he shocked the cycling world by returning to win the Tour de France again, ten years after his first victory. No other cyclist has achieved that feat.

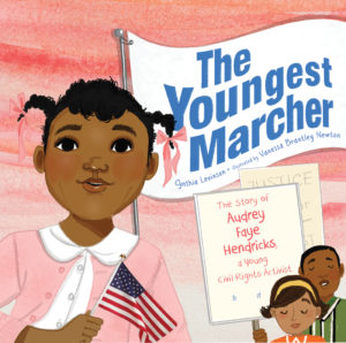

Bartali was known as a fierce competitor up until he retired at age 40, after being injured in a road accident. He was somewhat of a loudmouth on the cycling circuit, but modest about the fact he's credited with helping save the lives of hundreds of people. The story did not come out before he passed away in 2000. Biographer, Ali McConnon told CNN, "He was very modest about it. He held a profound sense that so many had suffered in a much greater capacity than he had. He didn't want to be in the spotlight or diminish the contributions of others." Bartali rarely spoke of his actions in the war. When asked by another reporter to recount his greatest victory, Gino said, “I won the challenge of life, winning the love of the people.” Now, there's a man who's inspiring in a good number of ways!  You may remember me writing about Audrey Faye Hendricks several years ago. She was nine-years-old, when arrested and sent to jail during a civil rights march in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. I'm excited to tell you about a new book about Audrey, a picture book for primary grade children about an incredibly brave third grader. The Youngest Marcher, by Cynthia Levinson tells the story of the Birmingham Children's March through the eyes of one little girl. Audrey's family was friends with Dr. Martin Luther King, and she was inspired by his talk about justice. Dr. King considered Birmingham the most violently racist city in the country, and he spoke in churches there urging blacks to march in protest of segregation, even though they'd be arrested. "Fill the jails!" said Dr. King.

The plan seemed risky to adults, who feared they'd lose their jobs, be assaulted or possibly killed. Few stepped up. When Civil Rights Leader Reverend James Bevel, suggested school children should march and go to jail, Audrey was one of the first to volunteer. Some four-thousand young people marched, and kept marching until Birmingham's jails were filled to capacity. Audrey spent seven days in custody, the youngest known child arrested.  The Children's March was powerful, helping gain momentum for civil rights across America. Two and a half months later, Birmingham rescinded its segregation laws, and a year later Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Cynthia Levinson's earlier book We've Got a Job: The 1963 Birmingham Children's March tells Audrey's story in more detail, as well as the stories of three other young marchers. In my 2014 post, here's what Cynthia had to say about the courage of those young civil rights activists: When I tell school children today about the brave youngsters in Birmingham, they want to know if I would march, too. Would I sing and pray? Would I face dogs, hoses, and jail? The reason that I know, unfortunately, that I would not is that I did not. In May 1963, I was an eighteen-year-old high school senior in Columbus, Ohio. In fairness, not a single white person joined the black children during their protests in Birmingham so it’s not completely surprising that I didn’t fly down there. (Some white clergymen and the folk singer Joan Baez did, however. Nevertheless, to the extent that I paid attention to the news, I was bewildered by what was happening down there. Worse, I hardly paid attention at all. In fact, although I knew about the dogs and the hoses, I didn’t know that it was children who took responsibility for desegregating their city until decades later. Furthermore, although later I did participate in a few protests about political issues I cared about, I chose tame ones where no one was going to get hurt. Because we know how events in the past have turned out, history in hindsight looks inevitable. Young people today could believe that the children of Birmingham weren’t in any real danger. Beforehand, however, Dr. King was so worried that someone might get hurt or killed that he opposed their actions. Sharing my own embarrassing past with them, I think, makes the threats more real. These were truly dangerous times. Courage, I hope they learn, does not entail ignoring the dangers but, rather, paying attention to them—and then making a decision about whether or not to proceed. Courage, I’ve learned, is not casual. Courage requires a cause. And, courage draws strength from cooperation. Thank you, Cynthia! So well said. Learn more about Cynthia and her books here...  I also want you to meet the very talented illustrator of The Youngest Marcher, Vanessa Brantley Newton. (at left) She says "The beauty of the book is that little children will walk away with- 'I can do something, no matter how small I am, there is something I can do.' That's empowering." Vanessa demonstrates how she illustrated the book in a live video interview here.... It's amazing to watch her draw! She's fun to listen to, too. Vanessa is a prolific illustrator. Check out more of her work here... |

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|