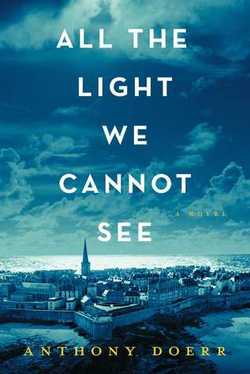

Through a stroke of luck, I heard Anthony Doerr read the first few short chapters of ALL THE LIGHT WE CANNOT SEE at a literary festival in Spokane last year. I was hooked by the specificity and beauty of his writing, and the tension of the story. Still, I put off reading the book all year while it became a finalist for the National Book Award; a #1 New York Times bestseller; was named a best book of the year by the New York Times Book Review, Powell’s Books, Barnes & Noble, NPR’s Fresh Air, Entertainment Weekly, the Washington Post, Seattle Times and the Guardian, just to name a few. I feared a tragic ending, after all, it’s a war story. I finally overcame my trepidation, and now I highly recommend the book. It touches on all the grand themes of life that we struggle to understand. It’s the story Marie-Laure, blind from the age of 6 who lives with her father in Paris, where he is a locksmith at the Museum of Natural History. The museum is her second home as she grows up, learning the mysteries and beauty of nature through her fingertips. She was particularly fascinated by one professors collection of shells. Dr. Geffard teaches her the names of shells--Lambis lambis, Cypraea moneta, Lophiotoma acuta--and lets her feel the spines and apertures and whorls of each in turn. He explains the branches of marine evolution and the sequences of the geologic periods; on her best days, she glimpses the limitless span of millennia behind her: millions of years, tens of millions of years. Intertwined with the girls’ story is that of a German orphan boy Werner, incredibly bright, but trapped in a mining town that produces raw materials for the Nazi war machine. Werner is 8-years-old when he discovers a rudimentary radio in a junk heap. For three patient weeks, he studies it and works on it until he gets it to work. Open your eyes... The only legal radio programs spout Nazi propaganda, but Werner secret listens to a Frenchman broadcast of a science lesson for children. Open your eyes, concluded the man, and see what you can with them before they close forever, and then a piano comes on, playing a lonely song that sounds to Werner like a golden boat traveling a dark river, a progression of harmonies that transfigures Zollverein: the houses turned to mist, the mines filled in, the smokestacks fallen, an ancient sea spilling through the streets, and the air streaming with possibility. It is these tenuous radio waves that eventually connect Marie-Laure and Werner, though it is years later when she is a 16-year-old working with the French Resistance and he is a soldier in the German Army using his gift for math to root out illegal radio transmitters.  Walled city of Saint-Malo occupied by Germany in WWII Walled city of Saint-Malo occupied by Germany in WWII Marie-Loure and her father have fled Paris for the walled city of Saint-Malo on the coast of Brittany. Throughout the book we “see” from the point-of-view of the blind girl, but here at the ocean, her perceptions become especially keen as she encounters the live creatures that were empty shells in the museum. The reader is reminded of words Werner heard over the radio years earlier. The brain is locked in total darkness of course, children, says the voice. It floats in a clear liquid inside the skull, never in the light. And yet the world it constructs in the mind is full of light. It brims with color and movement. So how, children, does the brain, which lives without a spark of light, build for us a world full of light?  On his website, Anthony Doerr explains the meaning of the title, All The Light We Cannot See. It’s a reference first and foremost to all the light we literally cannot see: that is, the wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum that are beyond the ability of human eyes to detect (radio waves, of course, being the most relevant). It’s also a metaphorical suggestion that there are countless invisible stories still buried within World War II — that stories of ordinary children, for example, are a kind of light we do not typically see. Ultimately, the title is intended as a suggestion that we spend too much time focused on only a small slice of the spectrum of possibility. - from Doerr’s site So, yes, it ends as a war story often ends, but the read is worth it. I recommend it to older teens as well as adults. The relationship between Marie-Laure and her father, and that which she develops with her great-uncle Etienne are transformative and the book is worth reading for them alone, but there is so much more that is difficult to put into words. The intricate structure crafts myriad threads together, a haunting and spectacular weaving of the highest and lowest of human nature. Have you read it? What do you think? With much thanks to Aria Antiques, Curious Expeditions, San Fransisco, CA Comments are closed.

|

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|