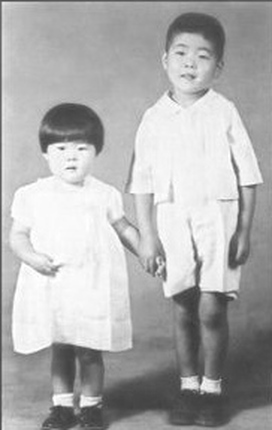

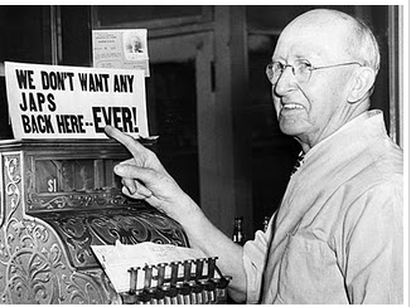

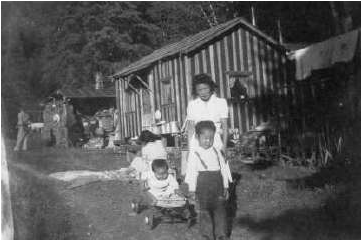

Following Pearl Harbor, racist fear and resentment exploded against Japanese Canadians in British Columbia. "It is the government's plan to get these people out of B.C. as fast as possible," said Cabinet Minister Ian MacKenzie. "It is my personal intention, as long as I remain in public life, to see they never come back here. Let our slogan be...No Japs from the Rockies to the seas." Six-year-old Joy Kogawa and her brother were separated from their father and grandparents and herded onto a train with an aunt & uncle. The train carried them to Slocan City, a long played-out silver mining town in the foothills of the B.C. Rockies. Joy choose one doll to take with her. The outcasts were allowed only what they could carry to build a life in a two room shack with no plumbing or electricity. The family's home in Vancouver, BC and all it’s furnishings were confiscated and later sold for a tenth of their value. Royal Canadian Mounted Police yanked men away from their livelihood, fishing boats and gear confiscated, their life on the temperate coast exchanged for the harsh conditions of inland roadwork camps.  Canadians have a great reputation. In fact, for three of the last four years running the Reputation Institute reports Canada has been the most beloved country in the world. Maybe that's why it was such a shock when I discovered Canada, like the United States, treated its Japanese citizens so shamefully during World War II. Reading a novel based on these events, I nearly had to put it down, it was so awful. But as is often true, I found the story of a woman who survived horrible hardship and injustice, and somehow spun straw into gold.  Thanks to George Fukuhara for photo. Thanks to George Fukuhara for photo. Many women, children and elderly were rounded up and housed for months in an over-crowded livestock exhibition building, before being shipped off to shanty towns and internment camps. At right, Fumiko Fukuhara with two of her children in front of their tar-paper shack near Tappin B.C. Nearly starving the winter of 1942-43, they found a farmer, Henry Calhoun farm willing to give them work on his vegetable farm. Twelve-hundred fishing boats were taken from Japanese Canadians. After WWII, Joy and her family hoped to return to their home and life in Vancouver where her father had been a doctor. Instead they were hauled even further from home, over the Rocky Mountains to a sugar beet farm near Lethbridge, Alberta. They lived in a one-room hut with their aunt & uncle, toiled in the beet fields during the blazing summers and traded places near the stove during the freezing winters. Joy Kogawa wrote a novelized version of her experiences during this time. In Obasan, she speaks of those years on the sugar beet farm.  Photo thanks to Dan Toulgoet, Vancouver Courier Photo thanks to Dan Toulgoet, Vancouver Courier But the nightmare grew even worse. Years later, Joy discovered her mother, who had been visiting Japan when the war broke out, was in Nagasaki when the U.S. bombed the city. Next week, I'll tell you about Joy's journey through "personal hell" to find mercy. Her novel Obasan is now required reading in many schools across Canada, and has been called one of the country's all-time best 100 books. “The fact is, I never got used to it, and I cannot. I cannot bear the memories. There are some nightmares from which there is no waking.” Click here to read part two...Comments are closed.

|

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|