|

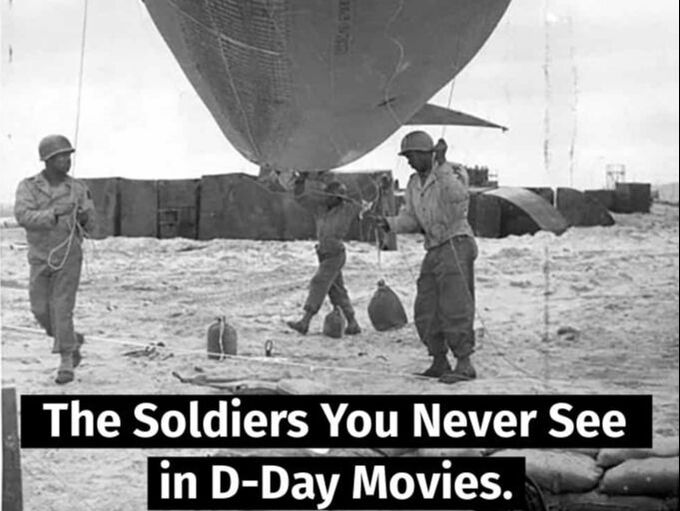

I had no understanding until recently of "barrage balloons" nor their importance in the success of the Normandy invasion. And further, I had no idea of the crucial D-Day role played by black soldiers landing on Omaha Beach. This bit of forgotten history was brought to my attention by long-time newsletter reader Norm Haskett. Norm is the creator of the incredible website The Daily Chronicles of WWII, possibly the most thorough collection of WWII information on the web. Who better to fill in for me this week while I'm on vacation? Thanks so much, Norm, for giving us this opportunity to remember D-Day, the brave men who gave their lives, and those who survived the brutal landings on Normandy beaches. Of the 57,500 U.S. soldiers who landed on Normandy’s Omaha and Utah invasion beaches in Northwestern France on June 6, 1944, fewer than 2,000 were African Americans. Unique among these black servicemen were 621 men who, from their complement of 1,500 black soldiers and 49 white officers, comprised the initial assault force of the First U.S. Army’s 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion. The 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion’s extraordinary service was to defend Normandy’s fragile beachheads from enemy low-level strafing and bombing aircraft. The balloons forced enemy aircraft to fly at higher altitudes making them better targets for larger caliber anti-aircraft gunfire. The cables that anchored the balloons to the ground were very difficult to see and posed a risk to any aircraft that flew into them. An aircraft caught in a cable could be slowed down enough to stall and crash or have a wing torn off. The men of Headquarters Company and Battery A began landing on Omaha Beach at 9 a.m., a little more than two hours into the June 6, 1944, Allied invasion of German-occupied France. Battery C began splashing onto adjacent Utah Beach on the same day. Their work began after dark when a dozen bullet-shaped, steel-cable-tethered, lighter-than-air barrage balloons were quickly filled with hydrogen gas and floated over Omaha Beach. Shot out of the sky by German artillery, none survived the morning. Later that second invasion day Battery B landed at Omaha with new barrage balloons, and the next evening were more balloons hovering over both invasion beaches. Their numbers swelled and swelled. The nucleus of D-Day’s 320th balloon flyers started training in December 1942 in the U.S. Jim Crow South. Sadly, in the early 1940s the U.S. Army was highly segregated. Black servicemen at the time were chiefly relegated to support roles in non-combat units where they served with honor, distinction, and courage as stevedores, truck drivers, and maintenance men. By 1944, 50,000 out of 700,000 black soldiers who entered the Army wound up serving as frontline troops: for example, on the ground as tankers in Lt. Gen. George C. Patton Jr’s Third U.S. Army’s all-black 761st Tank Battalion (“Black Panthers”) and in the air as the celebrated Tuskegee Airmen of the 332nd Fighter Group and 99th Fighter Squadron. Below is a rare daytime close-up photo of the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion in action. Battery A Cpl. A. Johnson of Houston, of Texas, with help from two men in his 3-man crew, walks an inflated 125-lb, 35-ft-long VLA (very low altitude) balloon toward a 50-lb winch that will float the balloon over Omaha Beach. The barrage balloons were made of two-ply cotton fabric impregnated by vulcanized or synthetic rubber and coated with aluminum. Most balloons were raised at night after Allied planes had returned to their bases in England. By June 21, 141 silvery orbs dotted the skies. This is how Normandy’s invasion beaches are remembered in the popular imagination. Sadly, the role of the segregated 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion never made it into cinematic retellings like Darryl F. Zanuck’s The Longest Day (1962) and Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan (1999). Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, lavished praise on the all-black balloon flyers who “proved an important element of the [U.S.] air defense team.” “I commend you and the officers and men of your battalion,” he wrote,” for your fine effort which has merited the praise of all who have observed it.” A newspaper reporter on Omaha Beach, referring to the 320th balloon crews’ floating minefield of barrage balloons, told his American audience that one of the Allies’ more unusual lines of defense was “one of the most important missions of the war.” Norm will feature a more in-depth article on the 320th Barrage Balloon Battalion on his website The Daily Chronicles of WWII. That goes live on June 7th. Here's the direct link: https://ww2days.com/all-black-battalion-raises-barrage-balloons-over-d-day-beaches.html. Clicking the link before June 7 will produce an error. Thanks again, Norm! Great story! A long-overdue retelling of D-Day’s black heroes appears in print and audiobook in Linda Hervieux’s Forgotten: The Untold Story of D-Day’s Black Heroes, at Home and at War. Just 7 days after D-Day more than 300,000 Allied troops, 50,000 vehicles, and over 100,000 tons of materiel had landed in France, and the five invasion beaches were fully under U.S., British, and Canadian control. Allied casualties on the first day were at least 10,000, with 4,414 confirmed dead.

Comments are closed.

|

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|