|

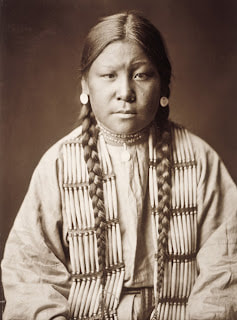

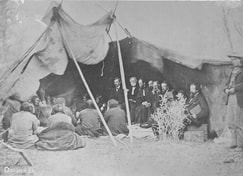

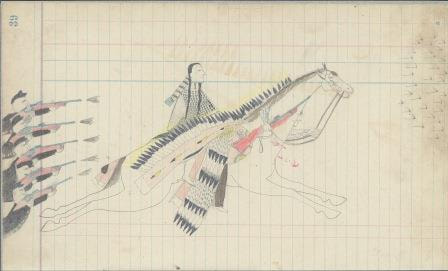

Yes, that Custer, General George Armstrong Custer killed in the 1876 Battle of the Little Big Horn. We know the men, Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, who whupped the general that day, but what of the women? The names and faces of the native women of the Great Plains are all but lost, erased from mainstream history. That's why the story of Buffalo Calf Road Woman is so important. It gives us a glimpse into the lives of native women at the height of the "Indian Wars," the US effort to subdue and corral the Plaines Tribes or annihilate them. There is no known photo of Buffalo Calf Road Woman. She may have looked similar to the unidentified Cheyenne woman in this photo, sometimes mistakenly identified as her. The Northern Cheyenne kept a vow of silence for more than "100 summers" until 2005, when a tribal elder stood up and told how Buffalo Calf Road Woman attacked Custer. One incident in the life of a young woman, a mother, and a warrior, who faced enormous adversity trying to survive, defend her family, her homeland, and her culture. Historians believe Buffalo Calf Road Woman was born some time in the 1850’s. Her life unfolded, beginning to end, amid the "American Indian Wars" (1854-1890), a series of battles, skirmishes, massacres and broken treaties on the Great Plains. The stakes grew so high for the tribes on the northern plains, former enemies, the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho allied in a united front against white expansion. Under the leadership of Lakota Chief Red Cloud, they decisively defeated the U.S. Army and forced Americans to negotiate for peace. Under the The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho agreed to settle on the Sioux reservation in what is now western South Dakota. In return, the US designated for the tribes unceded lands adjoining the reservation and extending past the corners of present-day Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana and North Dakota. “From this day forward,” the Ft. Laramie Treaty began, “all war between the parties to this agreement shall forever cease.” It promised the land to the native tribes for their “absolute and undisturbed use.” A Northern Cheyenne, Buffalo Calf Road Woman lived in this country with her husband Black Coyote, their daughter, and her brother, Comes In Sight. It was prime hunting grounds for what remained of the once-vast buffalo herds that had sustained Plains tribes for generations. In the heart of this land lay Ȟe Sápa (the Black Hills of South Dakota) and when gold was discovered there, the peace agreement was doomed. The die was cast for Buffalo Calf Road Woman. The young mother would become a warrior. Gold miners rushed to the Black Hills in violation of the Fort Laramie Treaty, and to avoid trouble, the US government sought to purchase the land from the Sioux. But the land fed and clothed them. The Sioux couldn't survive without the buffalo range. When they refused to sell, President Ulysses S. Grant launched a secret, illegal war against the Sioux and lied to Congress and the American people about it. The Grant Administration ordered tribes wintering in their villages throughout the Unceded lands in Montana and Wyoming Territories to report to the Sioux reservation by January 1876, or the army would come after them. Many bands including those led by Lakota chief Sitting Bull, Oglala chief Crazy Horse decided they would not retreat to the reservation where they feared their people would starve. In February, General George Crook marched his troops out to round-up reluctant natives. A large number of Sioux and Cheyenne, including Buffalo Calf Road Woman's family had settled that spring in the Powder River and Little Bighorn valleys. When news came in mid-March that Crook’s soldiers had burned a Cheyenne village, they prepared for war. With Crook on the move, the native warriors decided to strike first. They attacked and surprised the federal troops June 17 at Rosebud Creek in current-day eastern Montana just north of Sheridan, Wyoming. Buffalo Calf Road Woman would prove her bravery, and her place in history, at the Battle of the Rosebud, which raged for six hours over a series of grassy ridges cut with deep ravines. In the frenzy of combat, a bullet struck down the horse carrying Cheyenne warrior Comes in Sight. His sister Buffalo Calf Road Woman saw his trouble and did not hesitate. She charged into the fray, heedless of flying arrows and bullets. The young woman raced her horse alongside her brother, and Comes in Sight caught hold around the neck of her horse. Buffalo Calf Road Woman escaped the heat of the battle and keeping them both alive. Below, a drawing contemporary to her time shows Buffalo Calf Road Woman rescuing her brother beneath the blazing guns of federal troops. It's part of a collection of native drawings on ledger paper attributed to Spotted Wolf-Yellow Nose, an Ute adopted by the Northern Cheyenne, who is believed to have participated in the battle at Rosebud Creek. A description from the book "We, the Northern Cheyenne People" explains the horse’s split ears indicates that it is a fast one. The drawing shows Buffalo Calf Road Woman in an elk tooth dress, and her brother, Comes in Sight, wears a war bonnet. At Rosebud Creek, Sioux and Cheyenne warriors led by Crazy Horse made a surprise attack on General Crook’s force, both sides had roughly 1,200 fighters, making it one of the largest battles of the Plains. The tribes fought General Crook to a standstill, pulling back at sunset while the federal troops retreated to camp. Known as the Battle of the Rosebud in history books, the Cheyenne remember it as the Fight Where the Girl Saved Her Brother. After the battle, the Sioux and Cheyenne moved their families roughly 50 miles north to the banks of the river they called the Greasy Grass. The US Army called it the Little Big Horn. Eight days later, General George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry attacked the village. Buffalo Calf Road Woman joined the fight alongside her husband Black Coyote. Another woman at the scene reported, “Most of the women looking at the battle stayed out of reach of the bullets, as I did. But there was one who went in close at times. Her name was Calf [Road] Woman …[she] had a six-shooter, with bullets and powder, and she fired many shots at the soldiers. She was the only woman there who had a gun. She stayed on her pony all the time, but she kept not far from her husband, Black Coyote. ” Custer and all his men died within an hour of the attack, though the fighting continued another day further east along the winding river. In total, 268 federal troops, including General Custer, died in what turned out to be US Army's worst defeat in the "Indian Wars." The exact circumstances of Custer's death have long been debated and his body was not discovered until two-days later. But in June 2005, members of the Northern Cheyenne gathered to recount their tribe's oral history of that day. The story told names a female fighter, Buffalo Calf Road Woman, who knocked Custer from his horse amidst the battle, leaving him vulnerable to the two gunshots he suffered, one of which killed him.  At the 10-year memorial of the Battle of Little Bighorn, unidentified Lakota Sioux dance in commemoration of their victory over the United States 7th Cavalry Regiment (under General George Custer), Montana, 1886. The photograph was taken by S.T. Fansler, at the battlefield’s dedication ceremony as a national monument. (Photo by Transcendental Graphics/Getty Images) The Northern Cheyenne had never told their story before because they feared retribution from the U.S. government. And though The Battle of the Little Bighorn was a major victory for the indigenous tribes, reprisals did indeed come. The U.S. Army doubled-down on its efforts to hunt all resisting Native Americans and within a year, most had been rounded up or killed. But the fight had not left Buffalo Calf Road Woman yet. Two days after Custer and his men died, US troops arrived to reinforce the units still fighting and the Sioux and Cheyenne packed up their village and fled. Roughly 1000 Northern Cheyenne, including Buffalo Calf Road Woman and her family, eluded capture for nearly a year, hunting ever-decreasing game, and often fleeing their villages as soldiers attacked. During this precarious time, Buffalo Calf Road Woman gave birth to her second child. But the game had become so scarce, the Cheyenne were starving. Surrender seemed their only chance to survive. They surrendered at the Lakota reservation in Nebraska where they thought they'd be safe. But U.S. soldiers forced them to march south, fifteen hundred miles in the summer heat to Fort Reno in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) where they were locked up. Conditions were horrible. Buffalo Calf Road Woman and her people barely survived on short rations handed out by the US government, and many were sick with malaria and dysentery. Two chiefs, Dull Knife and Little Wolf knew they must lead their people home to Montana Territory, or they would die. In September 1878, 350 Cheyenne escaped Fort Reno and headed north. Knowing army troops were coming after them, they hid by day and traveled at night. One night they entrenched themselves in the bluffs above a creek at Punished Women's Fork near current-day Scott City, Kansas. This is the next footnote in history that names and locates Buffalo Calf Road Woman. In this little valley they rested and hunted for food, and readied fortifications in a box canyon to ambush the troops on their trail. Soldiers attacked September 27, 1878. Children, the elderly and most of the women took refuge in a cave on the hillside. Buffalo Calf Road Woman joined the fight "[with] a gun in her hands, ready, the baby tied securely to her back." The Battle of Punished Woman's Fork was fierce, the lieutenant colonel leading the army was mortally wounded, but the Cheyenne eventually had to run. Slipping away at night, heading north on foot, they heard the gunshots that killed their horses. They evaded US forces and reached familiar country in Nebraska. Winter was coming and not everyone was strong enough to continue walking north. Buffalo Calf Road Woman joined the fight '[with] a gun in her hands, ready, the baby tied securely to her back.' (click to tweet) The group split up. Those too weak to spend a Nebraska winter foraging for food and always on the lookout for soldiers would continue the short distance to the Red Cloud Agency. Dull Knife, nearly 70, believed they could slip in and hide among the Lakota. The remaining 123, including Buffalo Calf Woman and her husband would winter over and resume their journey to the high plains of Montana Territory in the spring. A blinding snowstorm soon hit Dull Knife’s band and they ran into an army patrol. From the soldiers they learned the Red Cloud Agency had been moved to the Dakota Territory, and all that remained was Fort Robinson. Reluctantly, Dull Knife surrendered and his people moved into the barracks. In late February, with a break in the weather, Little Wolf’s people, including Buffalo Calf Road Woman again picked up their journey home. The army sent a man who had known and respected Little Wolf to intercept the band. Lieutenant William P. “Philo” Clark trailed the Cheyenne to the area of current-day Miles City, Montana, and convinced him to surrender. I don't know, but can imagine, Buffalo Calf Road Woman, holding her children close and listening to Little Wolf surrender. Or perhaps she heard the news later. Little Wolf told Lt. Clark: You are the only one who has offered to talk before fighting, and it looks as though the wind, which has made our hearts flutter for so long, would now go down. I am very glad we did not fight and that none of my people or yours have been killed. Buffalo Calf Road Woman's people turned themselves in to nearby Fort Keogh in Montana, where some 300 Cheyenne were already in custody. Buffalo Calf Road Woman lived her final days at Fort Keogh. History notes that she died from diphtheria the winter after she arrived, 1879. At most, she would have been 29. Today, children of the Northern Cheyenne nation learn about and remember their ancestors, men and women, who fought so courageously, defending their families, their land, and their culture. There are more than 12,000 enrolled tribal members, about 6,000 who live the Northern Cheyenne reservation in present day southeastern Montana. Every winter a special event pays tribute to the group of Buffalo Calf Road Woman's people who ended their journey in army custody at Fort Robinson. Under pressure to return to Oklahoma, in 1879, about 130 starving Northern Cheyenne people, mostly elderly, women and children made a break from the fort, hoping to make it hundreds of miles to their homeland in Montana. Pursuing soldiers massacred many that night and chased down another several dozen and killed them two weeks later. A small band led by Chief Dull Knife escaped and survived near starvation walking north in the dead of winter to arrive safely in Lame Deer, Montana, where the Northern Cheyenne Reservation would be created five years later. Now, each January 9th, 0:30 at night, on the actual date and time of the Northern Cheyenne breakout of Fort Robinson, children retrace and understand the journey of their ancestors from Nebraska to Montana. Through blistering winds, rain, snow and subzero temperatures, Northern Cheyenne youth from elementary to high school age complete the 400-miles in legs, handing off their Nation's flag and an eagle feather staff. Starting in Crawford, NE, they soon reach a snow-filled creek bed they call “The Last Hole.” In this desolate ravine, two weeks after the escaped from Fort Robinson, 32 men, women, and children, who had survived the initial massacre were hunted down and killed by US soldiers. Cinnamon Spear first made the run as a high school senior. “Going to where everything happened, you’re standing where the blood of your ancestors was shed. Your feet are where their blood was. You realize you are breathing the air of the land that holds those stories....You cry for kids your age who were shot. But there’s also hope, because you realize their courage allows us to be here and do this. Their sacrifice brought us here.” The run, five days and nights, continues passing a number of battle sites including The Little Bighorn Battlefield. It ends at a hilltop burial ground in Busby, MT, where their ancestors’ remains now lie, repatriated in 1994 from a Harvard University museum. I love night running,” said high school student Sharlyce Parker in January 2018. “I feel the presence of my ancestors. It’s like they’re running with me.” In the past 25-years, Fort Robinson Outbreak Run has grown beyond honoring their ancestors and become an opportunity for healing and wellness; youth leadership and empowerment; cultural & language preservation; environmental justice; and creating social change in Cheyenne communities. Each year about 100 youth participate, but due to covid in 2021 only 30 made the run. Check out their story with terrific photos click here. Sources https://helenair.com/news/state-and-regional/northern-cheyenne-break-vow-of-silence/article_a7a4a082-13a2-5da8-98ab-95517fac5ff5.html https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ulysses-grant-launched-illegal-war-plains-indians-180960787/ https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/502013/retrobituaries-buffalo-calf-road-woman-custers-final-foe https://truewestmagazine.com/rosebud-gets-no-respect/ https://www.ndstudies.gov/gr8/content/unit-iii-waves-development-1861-1920/lesson-4-alliances-and-conflicts/topic-2-defending-lakota-homelands/section-5-battle-rosebud-and-little-big-horn http://montanawomenshistory.org/a-young-mother-at-the-rosebud-and-little-bighorn-battles/ https://www.astonisher.com/archives/museum/who_killed_custer.html#part1 https://www.pameladtoler.com/ (Women Warriors) https://www.jstor.org/stable/777193 (Yellow Nose Ledgers) https://sova.si.edu/record/NAA.MS166032? https://www.yellowbirdlifeways.org/fortrobinsonrun https://indiancountrytoday.com/archive/running-to-remember-fort-robinson-outbreak-spiritual-run-completes-19th-year https://billingsgazette.com/news/local/photos-northern-cheyenne-hold-25th-annual-outbreak-run/collection_04eb03bb-dc97-5244-96c8-54b7f000566f.html#3 https://www.historynet.com/little-wolf-sweet-medicine-chief.htm https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/cheyenne-homecoming If you like the story of Buffalo Calf Woman please share with your friends and family. Comments are closed.

|

I'm fascinated to discover little-known history, stories of people and events that provide a new perspective on why and how things happened, new voices that haven't been heard, insight into how the past brought us here today, and how it might guide us to a better future.

I also post here about my books and feature other authors and their books on compelling and important historical topics. Occasionally, I share what makes me happy, pictures of my garden, recipes I've made, events I've attended, people I've met. I'm always happy to hear from readers in the blog comments, by email or social media. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|